AFOOT IN CHILE

A collection of U.S. newspaper articles written by "James A. Rankin"

Alias "J. A. R." alias "Quito"

(1) Voyage

from New York to Valparaiso (1856-57) 2

Letter "I"

Letter

"II"

(2) First

Wanderings in Chile (1857)

14

Letter

"VI"

Letter

"VII"

Letter

VIII

Letter

IX

Letter

X

Letter

XI

Letter

XII

Letter

XIII

Letter

XIV

Letter

XV

Letter

XVI

(3) Second

Wanderings in Chile (1858)

61

Article

One

Article

Two

Article

Three

Article

Four

(4) Farewell

to Chile (1858)

90

Final

Letter

ANNEX

Reminiscences

of Chilean Travel (1859) 99

APPENDICES

One:

Glossary of Spanish Terms

115

Two:

Bibliography & Sources

121

SECTION (1)

VOYAGE FROM NEW

YORK TO VALPARAISO (1856-57)

by

"QUITO"

These articles were published in the "Illinois State Journal" between May and December 1856.

LETTER "I"

Voyage Commenced—Last View of Land—Sea-sickness—A

Calm—Terrible Storm upon the deep—Ship Disabled—Gloomy

Night—Turn from the destined Port—Vessel Leaking—Cargo Thrown

Overboard—Pleasant Weather—Enter the Tropical Waters—Glorious

Sunrise—Baffling Winds—Fair Wind—Land, ho!—Panorama of

the Islands—Lovely Scene—"Hard up the Helm"—Vessel

on the Rocks—Carried off by the Flood-tide—"Drop the

Anchor."

St. Thomas, W. I., March 31, '56.

I arrived in the city of New York on the

last day of the year 1855, and for more than two months awaited the sailing of

a vessel to Valparaiso. But the longest delays have an end — at least so

I thought when the steam tug came alongside to tow us out to sea.

At an early hour on the morning of the 5th of March, I took

my last stroll up South street, supplied myself with the morning edition of the

city papers, and returned to the little ship, which I then thought would be my

home for many long and weary weeks. Before eight o'clock, the passengers and

crew — the former six in number —were on board; and, at 8:50, the "Sophia

Walker", Captain C. R. Moore, dropped down from Pier 37 East River. The

American flag was unfurled to the breeze, the parting gun fired, the farewell

cheer given by friends on shore, and heartily responded to by the crew, when I

felt that my journey had commenced; whether it would be long and adventurous,

time alone could determine.

The city, with its forest of masts in the

foreground, lessened in the view, and Staten Island with its romantic hills,

crowned by many a lovely villa, and robed in the mantle of winter, rapidly

receded in the distant perspective. At 11:45 the pilot was discharged, and,

with a jolly crew and lively passengers, our ship stood boldly out toward the

boundless horizon on her intended voyage around Cape Horn. I watched the

Highlands of Neversink, as many a voyager had done before, until they faded in

the dim distance. An intervening wave would hide them for a moment from view,

another, and they were visible; but soon the last material tie that bound me to

my native land had disappeared. I could not see this and the white capped waves

close around us without an emotion I never felt before. The evening was

beautiful, a few light clouds floating in the distance, while the ship, with a

fair wind and a swelling canvass, went bounding over the wave.

I turned out of my berth in the morning at

an early hour; it was a glorious morning upon the mighty deep. A fine breeze

was blowing from the South; and, as our ship moved along at the rate of nine

knots an hour, the rippling waves at her sides and bow flashed with phosphoric

light. But sea-sickness prevented my enjoying scenery or anything else. Three

mortal days were passed in almost hopeless agony. It was not until the 9th that

the demon left me, certainly without regret on my part. The weather during this

day was fine, though not favorable to the vessel's progress. The wind lulled

down to a calm in the afternoon, the sails flapping idly against the masts. The

moon and stars at night shone brightly through the deep blue sky, occasionally

obscured by fleeting clouds. It proved, as the captain said it would, to be the

precursor of a terrible storm.

The following day — Monday, the 10th — was rough and stormy.

During the afternoon two frightful squalls came down upon us from the

Southwest; the howling of the wind as it swept through the rigging was fearful;

all hands were called to take in sail, the top-gallant-yards were lowered, and

the ship "laid to" to drift at the mercy of the waves. The gale, from

the Northwest, now commenced, and continued with unabated fury during the two

following days, but without any injury to the ship. It was reserved for

Thursday, March 13th, to roll the "tenth wave" of the storm down on

us. It was indeed an awful day, and one which I will not soon forget. Owing to

the long continuation of the gale, the sea was lashed as though a myriad

monsters of the unfathomed deep were engaged in deadly strife. The waves came

rolling on like mountains tumbled down, by nature's grand convulsion, their

snow-white crests boiling and hissing in waters of the brightest emerald green.

At one moment our little ship was borne to the summit of one of these Andean

billows of the watery waste, the next she plunged like a maddened steed down

into the dark valley of water below. But the disastrous effects of one of these

seas I have yet to relate. The passengers, including the captain and mate, were

seated at the supper table, the second mate had the watch on deck when a

towering wave came rolling down upon us in its mountain pride; on, on it came,

the frowning crest reaching to the foretop; the blow came with the most

stunning shock I ever felt, the ship trembled like a quivering leaf, the water

streamed upon our heads through the skylight, the lamps were put out, and the

dishes swept from the table quicker than thought. All then was still for a

moment; it was a moment of awful suspense, for the ship, completely buried in

water, seemed to be going down. Gradually she swung to the larboard side, and

we felt assured of at least a momentary safety. The cabin door was forced open

when everything on deck appeared to be in chaotic confusion; bulwarks stove,

deck covered with water, pigs scrambling in the briny flood, and every

impending wave seemed as though it would sweep us into a watery grave.

A gloomy night succeeded the day, more

terrible because of the darkness. Its experience I do not care about repeating.

Our brave and experienced captain was even appalled at the terrible scene;

which during the twenty-four years of his voyaging upon the ocean, exceeded any

storm he had ever witnessed. Owing to the damage the vessel had sustained, the

captain shaped her course the following morning for St. Thomas for repairs —

distant twelve hundred miles. Already she had sprung a leak, which rapidly

increased as the day advanced; two pumps were kept going constantly; this state

of affairs was indeed alarming. A consultation was then held; the captain said that

if, in our present condition, another gale should spring up the ship must

inevitably go down; our only hope of safety was to have the vessel lightened,

and the sooner done, the better. Passengers and crew were then told if they had

any objection to such a course, to offer them — of course none were

offered. The main hatch was then opened, and we commenced throwing the cargo

overboard considerably faster than it was taken in. In the course of three or

four hours we had discharged about fifty tons; as this materially relieved the

ship, the hatch was closed up again, the water pumped from the hold, and we

rested from our labors, much relieved in mind from the pleasant appearance the

weather was assuming.

The following morning, Saturday 15th, dawned

bright and beautiful upon the ruffled waters. There was a clearness in the sky,

and a purity in the air, I had not seen and felt since the day we sailed. A

lovely breeze was blowing from the northeast, which the captain hoped would

take us to the "trades;" the "stormy region" of the Gulf

stream was left behind, and from this date the weather was pleasant. Day after

day passed quietly away. The monotony of the scene was occasionally broken into

by the view of a distant sail, or a school of flying fish, as they skimmed over

the surface of the water.

The summer-like beauty of the air, as we

neared the tropics was striking. This was more especially the case at night,

when the full-robed moon bathed the light fleecy clouds with a soft and mellow

glow, and the dancing waves reflected her rays as from a thousand mirrors.

Our ship hovered on the verge of the tropics

for several days, as though reluctant to enter the fiery flood. The latitude by

noon observation on the 25th, was 22 deg. 54 min.; hence, we must have crossed

the tropic of Cancer during the night. I rejoiced in the thought of being

within the limits of the torrid zone. The boundless sea gave no evidence of the

fact; but I knew within its bosom there reposed this gorgeous scenery of a new

world.

I was roused at an early hour the next

morning by the sailors singing one of their cheering songs as they pulled at

the ropes. Day was beginning to dawn behind the dark clouds which were piled in

irregular masses against the eastern horizon; long radiating streams of an

alternate rosy azure hue soon shot towards the zenith; and as the minutes

advanced, the light wavy tufts of cirrus far above the frowning ramparts below

glowed and flamed like burnished gold; the rough and ragged edge of the dark

mass was illuminated with a crest of the most dazzling brilliancy, when the sun

arose above the whole, a fitting finale to the aerial painting.

Our progress was now retarded by baffling

winds. The "trades" which the captain so confidently counted upon,

appeared to have their direction reversed, and for two or three days it was a

"dead beat," as the sailors term it. On the 29th, the wind lulled

down into a calm in the forenoon, but as the day advanced, a light favorable

breeze sprung up, increasing in strength during the night, until the water in

the ship's wake fairly boiled with phosphoric fire.

I turned out of my berth in the morning, Sunday March 30th,

at an early hour, and found the captain already on deck keeping a sharp look

out for the long-expected land. The morning light had barely dawned, when he

told me he could see the distant coast. I looked with a beating heart across

the wide water, in the direction pointed out, when, sure enough, dim and

shadowy against the western sky, stood the first tropical land I ever beheld.

It proved to be the island of Virgin Gorda, one of the group of the Virgin

isles. The ship, with a fine breeze, was sailing along at a rate unknown for

days before, and, as we neared the island, its rough fantastic cliffs glowed as

with a fierce internal heat. The southern part of the island was inhabited, for,

with the telescope, I could see houses and plantations, and even the roads as

they wound their serpentine courses around the mountains in the interior. On

the extreme southern part of the Island, lone and solitary in its tropical

beauty, stood a single cocoanut tree.

The captain allowed the vessel to run as

close to the shore during the day as safety would admit; and what a glorious

panorama was unfolded to the view! It is true that no gorgeous vegetation robed

the island sides with the undying green of the isthmus; but as island rose

above and beyond island, with many a little bay and cove indenting their

coasts, showing that beautiful gradation of tint, of picturesque form and

varied shade, which distance alone can give, I felt that my imagination had not

been allowed too free a rein, in painting the charming beauties of island

scenery. I longed to go ashore and roam over the hills and mountains, and

explore the mysterious caves which were occasionally to be seen in the rocky

shores, telling a tale of the pirate cruisers that once swarmed in the waters.

As we were passing a lofty pile of rocks, which were cut off from the main land

of one of the islands, my attention was called by the mate, to a century-blooming

aloe, perched on the topmost cliff. I was struck with the incident. Generations

were to pass away from the time it first kissed the ocean breeze, till it

should bloom and then, 'twould "blush

unseen, and waste its sweetness on the desert air."[1]

Night closed upon the beautiful scene. The

clouds, which during the day had overhung the land, disappeared with the

setting sun, and the stars shone forth with a lustrous brilliancy known only to

a tropical sky. The dark outline of the island of St. Thomas loomed up on our starboard

beam; I could hear the roar of the surf, and in the dim starlight could

distinguish the dark patches of vegetation which dotted the gentle shores. A

fresh breeze was blowing from the land, bearing with it the sweetest fragrance

I ever breathed. I could almost have imagined myself in the gardens of Isfahan.

I never in my life before experienced such enjoyment; we had been tossed upon

the ocean's angry breast, and were now almost within hail of the wished-for

port: for although I love the ocean, and during the terrible storm could read

and appreciate Byron's Apostrophe, the land, from the Andes to the Himalaya, is

my home. I felt that deep and placid excitement that the traveler alone can

realize, but which language cannot express. I did not see the dark cloud, whose

murky folds were destined to wrap this lovely scene in momentary gloom. It was

best that l did not.

I was standing on the quarterdeck, leaning

against the rigging, and watching the lights in the city and harbor, as they,

one by one came in view, when I heard the order of the captain to "hard up

the helm," in that sharp quick tone which indicated danger; almost

simultaneously with the order, the ship struck, and after dragging a few

fathoms, came to a stand, save that she thumped on the rocks in a manner

anything but agreeable. The boats were ordered to be lowered, which was done as

soon as possible, the second mate and four men jumped in one, and taking three

of the passengers, the cook and steward, and such few articles as could be picked

up at the moment, pulled for the town, distant nearly two miles. The remaining

passengers, Capt. Valin, Dr. Scammon and myself, determined to stay with the

captain and the remainder of the crew, until the vessel was got off or went to

pieces. We had the largest boat at the side, and were ready to leave the ship

at a moment's warning. As soon as the second mate's boat left the ship, the

cannon were fired as signals of distress, and sail made in order to force her

off if possible. Fortunately the tide was rising, and after grinding her keel

on the rocks for about two hours, she gave a thump which jarred every timber in

her, and then swung free of the treacherous ledge. Up to this time there was

only three feet of water in her hold; a ship of ordinary strength would have

broken in two. An English war steamer was lying in the mouth of the harbor;

and, as we steered up toward the town, we were successively hailed by her and

the fort.

At twenty minutes before twelve the order

was given to "stand by and let go the anchor" a harsh grating sound

ensued — when a voyage short in duration, but replete with thrilling

incidents, was brought to a close. [2]

g

LETTER "II"

Detention in Rio—Priests, Church beggars—Brazilian

women—the Emperor—men-of-war's men—beautiful scenery tropical

garden—negroes—yellow fever—fleet of sail boats—the

"Iris" towed down the Bay to the guard ship—"who has the

papers?"—last view of Rio—"your pass!"—the

Portuguese captain, change among the crew—favorable

winds—"Sunday sail, never fails,"—encounter a

"pampero" off the Rio de la Plata—Cape

pigeons—calms—Staten Land and its snow-capped

mountains—Magellan clouds—snow squalls and Cape Horn

gales—double the Cape—"the ship is

sinking!"—placidity of the Pacific—the Chilean coast—end

of the voyage, &c, &c.

Valparaiso, Chile, S. A., September 27, 1856.

The "Iris" was detained at Rio de

Janeiro for a period of two weeks, discharging her cargo and taking in more

ballast. I will take the jottings down of the incidents of a week, from my

journal, and then proceed to the principal events of my voyage, which at length

is brought to a close.

Sunday, August 10. Another interesting week

has passed away. I have been ashore every day last week, with the exception of

Tuesday, and the long ramble through the city last Monday fatigued me to such

an extent that I was fain to stay aboard and recruit myself on that day. My

general impression of Rio is favorable in nearly every respect; I have had one

obstacle in my way however, and that was, ignorance of the language; still I am

very well satisfied, and if I have not seen as much of Rio as I could have

wished, I can say that I have seen, considering my opportunity, no small amount

of life and scenery. In wandering around I have seen quite a number of priests;

a strong proof, if one were wanting, that I was in a Catholic land. I saw, last

Monday morning, two or three church beggars going around bare-headed, with an

umbrella spread over them. They had a light kind of gown thrown over their

shoulders to indicate their calling. I noticed that they stopped at nearly

every door and begged with an unblushing effrontery that was truly astonishing.

There was a great procession last Sunday night and it is likely that these

gentry were collecting means to defray the expenses.

With regard to the women of Rio I can say

but little, for I have seen but few of them; generally speaking, they are not

as handsome as my own country women, although I saw some beautiful faces by

taking a sly peep through open windows. I was walking along one day near the

suburbs in a winding kind of a street, when I saw a pretty little brunette

looking out of an open window with her arms resting upon the sill; she was the

first pretty girl I had seen, and as I passed her I happened to look down at

her little arm, I regret to say that it was darker than necessary. I saw this

little witch again and I am not sure but that I should have seen her a third

time if I had remained in Rio. The Emperor visited the French frigate one day

last week; there was grand saluting on the occasion. I saw the foreign

ministers come off in the evening dressed in their brilliant uniforms. I did

not see his Majesty, much to my regret. After wandering around the city for

several hours, and tiring myself out, I would go down to the ship chandlery and

wait for the "Iris"' boat. Sometimes I would remain there an hour or

two and, as the men-of-war's men landed there, I had an excellent opportunity

of studying the various characters of the French, English and American tars. As

our second mate, who is an old man-of-war's-man himself, remarks, the French

are dirty, the English drunken, and the Americans proud. There is something

about the men-of-war's-men of all nations that is altogether different from the

merchant sailor. They have not that downcast look which is incident to hard

treatment.

I think there are some of the finest

glimpses of scenery in Rio I ever beheld. Some of the private residences that

are situated back from the business part of town are exceedingly tasteful in

their decorations; the polychromatic wreaths of flowers which adorn the

pediments of some of their villas, united with the general expression of the

whole, I could never tire in gazing upon. From these works of art the eye would

glance up to the summit of a lofty hill, and see, cutting sharp and clear

against the deep blue sky, masses of dark green foliage, or that type of the

South, the gorgeous palm. The gardens are in keeping with the rest of the

scenery, and many a little gem of beauty will long remain impressed upon my

memory. These remarks apply to the suburban portion of Rio, for doubtful sights

and smells are to be observed in the lower or business portion.

I also visited the tropical garden nearly

every morning during the week, and wondered at myself for passing by in a

former visit so much that was interesting. Upon the dark green leaves the dew

drops sparkled like a myriad of diamonds; sweet birds warbled their notes of

melody among the palms; and unknown flowers basked in the early sunlight. On

Thursday morning I took a sketch of a portion of the city of St. Sebastian from

the terrace of the garden. This terrace is elevated ten or fifteen feet above

the garden level, and is about thirty feet in width and nearly three hundred in

length. It is paved with black and white marble blocks, with an occasional

streak of granite. Close to each end of the terrace is an octagonal building,

for what purpose used I do not know. There is also one of these buildings in

the garden. The view of the garden from the terrace is a singular blending of

the beautiful and the picturesque. I imagined that with a certain addition it

would form an excellent sketch for an allegorical representation of the Dreams

of Youth. I lingered upon the terrace the morning aforementioned for a long

time; the heavy swell of the Bay beat against the wall with a crashing sound,

and when at last I turned away from the beautiful scene, I felt that its

charming influence had made me better than I was before.

There are many far different scenes in Rio.

I saw quite a number of beggars lying around on the narrow sidewalks. They were

really the most worthy looking beggars I ever came in contact with. The slaves

look contented and happy. I noticed that the faces of a large number of the

negresses were "tattooed;" they were probably natives of Africa. I

saw a poor old negress going about one day picking up sticks of wood. Poor old

thing ! I pitied her, for she was raggedness and attenuation personified. I

have understood that there is considerable yellow fever in Rio, and one morning

I met two soldiers on a corner carrying a sick man in a hammock who looked

rather suspicious about the eyes; but still I half doubt the tale. The

temperature of the air at this season of the year is from 70 to 75 degrees.

Nearly every morning a heavy fog envelopes the Bay, which is not swept away

until the sea breeze sets in. This is sufficient to make the place unhealthy in

the summer.

The "Iris" was hauled off to an

anchorage in the early part of the week, in order to give the French mail

propeller a chance to take in coals. The British steamship lay close by,

similarly engaged. There was a jolly set on the English boat during the night;

there was fiddling and dancing, and any amount of noise.

There are a great number of small sailing

boats in the Bay. Every morning they come in from the opposite side to the

city, laden with marketing, and in the evening the fleet returns. The

picturesque "felucca," a boat with two separate sails running to a

peak, and the Rio boat, with its single square sail, add much to the beauty of

the view upon the water. This Rio boat is hewed out of a log, and is generally

managed by two persons, owing to the size of the boat, who also row with

paddles.

The Captain came off at a late hour last

night, and gave such orders to the mate that I knew we were going to sail

to-day. He had told me late in the evening that he would not sail on Sunday

again, on account of his having bad luck last time— that is, a very long

passage; but I presume that he changed his mind. About half past seven this

morning a little steam tug grappled the "Iris," and towed her down

the Bay to the guard ship. The guard boat came alongside and demanded the

papers for inspection. The Custom House officer did not have them, the Captain

did not have them, no one had them. There was an evident misunderstanding. The

guard boat pushed off, the anchor was let go, and the Captain, in a terrible

rage, ordered the ship's boat manned, and started ashore himself to procure

them. He had not been gone more than five minutes, when they were brought

aboard in the ship chandler's boat, which had been cruising about an hour or

two in search of us. In the mean time, there was a great commotion in the Bay.

At a short distance a small steamer was careering around; her deck was covered

with officers and soldiers dressed in splendid uniforms, and the notes of a

brass band, softened by the distance, were borne across the placid water. A

Brazilian war steamer, surrounded by men of war boats, was also getting under

weigh near at hand. At the same time, the French screw propeller "Le

Lyonnais" came steaming down the Bay, while boats of every kind, and

manned by many a motley crew, added immensely to the general bustle.

The church bells were ringing a merry peal

when our captain returned; the papers were examined, the password given, the

anchor tripped, and the steam tug again made fast to us. I took the telescope

and scanned the city for what may be the last time. It was one of the few

mornings when no fog dimmed the beauty of the sky. Far away to the northwest

loomed the blue pyramidal head of an isolated mountain, whose sharp peaks were

almost blended with the northern sky. I bade farewell to Rio de Janeiro with

regret, for it had brought me more than I sought. I indulged the secret hope

however that I should again return. "We were soon close to "Santa

Cruz" when the sentinel on the walls shouted out "your pass !"

"Mar !" answered the captain "all right," was returned, and

we proceeded on our way without interruption, unlike an American ship that was

fired at a few days before. The captain ordered all the sails to be loosed, and

the topsails were sheeted home with merry songs. The steam tug was cast adrift

just as the sea breeze was setting in; her captain in broken Portuguese cried

out "fair winds," for which our captain thanked him, and with a light

wind we stood due South. About two o'clock P. M. we passed Raza or the lighthouse

island, beyond which Redonda reared its feathery crown of palms, and shortly

after the white reaches of sandy beach, like threads of silver, were hidden by

the dancing waves.

During the afternoon the breeze gradually

freshened, and the ship is now going nine knots per hour. The mountains that

surround the bay would still be visible were it not for the darkness; the last

glimpse I had of "Sugar Loaf" was at sunset. There is something of a

change in our crew, and there had like to have been a greater one; the Lopez

soldier and one of the boys took their departure without due notice being

given, but their places are well filled by an English boy and a Portuguese

sailor whose fine manly form and dark hair and whiskers remind me in a striking

manner of the picture I had formed in my mind of the great navigator, Magellan.

Favorable winds attended us for the three following days, and the captain

remarked to me on Wednesday evening that "Sunday sail never fails."

The same night the barometer commenced falling rapidly, and at five o'clock the

following morning the expected "pampero" struck us, and for forty

hours it blew a fierce gale from the west. The ship was "hove to"

under her storm sails and proved herself an excellent sea boat. Immense flocks

of Cape pigeons hovered around us during the gale. These birds are web footed,

and in other respects very much resemble the tame pigeons. I amused myself at

times in the very questionable employment of catching these birds with a pin

hook. The storm was succeeded by light winds and calms, but a fair wind

continually came to our relief, and on the 29th of August we made Staten Land

bearing nearly South. This Island lies to the north and east of Cape Horn and

separated from Terra del Fuego by the Straits of Le Maire. The wind was blowing

a steady gale from the northwest, and our ship was running in the trough of the

sea, but all the canvass was piled on her that she would bear, and for a few

hours she underwent the operation of diving.

The land indistinctly seen through the haze

at first, soon assumed a definite outline, and its snow-capped mountains cut

sharp and clear against the wintry sky. We ran about a league from the shore,

and, at the imminent risk of being well drenched, I stood up between the cabin

and bulwarks and took two sketches of that distant and desolate land. There was

a scanty vegetation perceptible upon its rocky sides, but the wild sea fowl

winging its rapid flight over the splintered rocks was the only living thing I

saw. Several large and massive rocks upon the summit of a lofty ridge, had the

exact appearance of castles with their battlements and towers, and I almost

looked for a race of giants to emerge from the imaginary portals of these

apparent strongholds. As we ran under the lee of the shore, the water was

comparatively smooth, and although the wind came direct off of the snow fields,

the thermometer did not indicate a lower temperature than 41ľ. A large cumulus

cloud rested over the Island, and the summits of the loftiest peaks were

wrapped in its dark and misty folds. The sun set behind the land, presenting

the most singular appearance imaginable; the night was blessed with a clear sky

and the southern constellations, and the Magellan clouds shone resplendent in

their quiet beauty.

The wind was fair during the night, and on

the following morning the Island was hidden from my view, but far away to the

northward loomed the snowy peaks of Terra del Fuego. The weather was so fine

that I hoped we would double the Cape without a gale; but the terrible storm king

of the south was determined not to let us off so easily; two or three light

snow squalls came out of the northwest, and then the wind hauled to southwest,

and in less than eight hours from the time the main royal was furled the ship

was "hove to." The howling of the wind as it swept through the

rigging on the night of the 30th of August was almost deafening. The ship

rolled and tumbled at such a rate that I got but little sleep, and in the

intervals of wakefulness I expected to hear the main topsail sheet part every

moment. I reconciled myself as well as I could to the tedium of a Cape Horn

trip life; and on the morning of the 12th of September, after two weeks of

baffling westerly gales, that tossed us about over the wild waters which had

been plowed by the keels of the adventurous Drake, and the intrepid Cook, we

doubled the celebrated promontory, and were fairly in the waters of the

Pacific. A fair wind which sprung up shortly afterwards gave us ten degrees of

latitude, but it gradually hauled ahead, and on the 21st, while blowing a

moderate gale with a short cross sea, a wave struck the vessel on her larboard

bow and stove her cutwater and did some other damage. The captain went forward

but soon returned and reported the ship to be in a sinking condition. This

would have been alarming news if true, but I was too well acquainted with his

disposition of making much out of a little, to believe any such a tale, and to

satisfy myself I went to the mate, who is not only a brave and skillful seaman,

but a truthful man; he quieted any apprehension I might have had for the safety

of the ship, by telling me there was no danger; personal inspection proved the

truth of his assertion. Had there been a party of ladies on board at the time

the captain made his announcement, I would much rather have been in the long

boat than in the cabin.

This was the last storm we had; a few hours

passed away and the wind came out fair, and in a day or two the waves faded

away to the gentlest swell, and I felt that our ship was in the Pacific Ocean.

I was charmed with the placid beauty of its waters, which move as smooth as an

inland lake. We made the coast of Chile on the 25th, and sailed in sight of

land during the day. Our ship was only two leagues from Valparaiso light house

when darkness closed around us. In the course of two or three hours we were

close to the shore, and not far off I saw the brilliant gas lights of the city

I had so long tried to reach, but which fate seemed to deny. The wind had now

died down to nearly a calm, and I laid down to sleep for the last time on the

good "Iris". The earliest streak of dawn found me peering over the

bulwarks, and admiring the opening beauties of the sweet 'Spring Chile.' The

morning breeze shortly freshened, and bore us up to the crowd of shipping, and

our ship was anchored in the bay where

"Valparaiso's cliffs and flowers

In mirrored wildness sweep." [3]

My long and varied voyaging and

counter-voyaging of sixteen thousand miles was thus brought to a close.

g

SECTION (2)

FIRST WANDERINGS

IN CHILE (1857)

by "QUITO"

These articles were published in the "Illinois State Journal" between May 1857 and March 1858.

LETTER

"VI"

Farewell to the "Iris", and her crew—Appearance of

Valparaiso, when viewed from a position in the Bay—View of the distant

Cordilleras and Coast—Range of Mountains—Scenery around

Valparaiso—Earthquakes—Native Chileans, their dress,

&c.—Singular Customs—Unrivaled beauty of the Climate.

Valparaiso, Chile, Feb. 28, 1857.

My last letter left me on board of the

"Iris," but my stay on the good ship, after her arrival here, was by

no means prolonged. For four long months, through sunshine and storm, had the

noble vessel been my home; but the hour came when I had to leave and again

encounter strange faces, and as I parted from the kind stewardess and

intelligent mate, and sung out a "good bye" to "old Jack,"

which was heartily answered, I felt sadder than I ever did before on a similar

occasion. Two or three days after, I ascended one of the cliffs and looked in

vain for the ship; she had sailed for another port. Will I ever again see her

tall and tapering spars, or tread her clean, familiar deck?

I will say nothing about my first impressions on coming ashore in this

place, save that they were not those of disappointment. Although the appearance

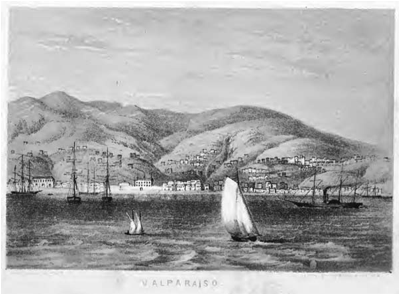

of Valparaiso when viewed from a position in the bay is singular, I cannot say

that the beautiful is blended with it. This is in a measure owing to the mean

appearance of most of the buildings, which are low, built of adobes and

tile-covered. Deep and precipitous ravines descend toward the bay, and up these

deep ''quebradas" a single

street will take its winding, tortuous way. There is, strictly speaking, but

one principal street in Valparaiso; it is about three miles in length, and in

its meanderings it assumes various names. To speak the truth, when I first

looked upon the cliffs and flowers of Valparaiso, it was not with that feeling

of indescribable rapture which I felt a few weeks before when I saw for the

first time that scenery which surrounds the "most

magnificent of all the havens of the earth."[4]

Ascending one of the lofty cliffs, which in

some places are almost perpendicular, and looking toward the North and East, we

have in view the Coast Range of mountains, distant some thirty or forty miles.

These mountains are from fifteen hundred to six thousand feet in height, and

when I came here in September many of them were covered with snow, but this has

long since disappeared. When the weather is fine and clear, beyond the coast

range can be seen the Cordilleras, white as Parian marble[5]

with the snows of countless centuries.

Conspicuous above all others, at the distance of ninety miles as the

crow flies, Aconcagua rears his lofty head more than twenty thousand feet above

the level of the sea. This mountain is, if we mistake not, the loftiest volcano

on the globe. It is now many years since it was in a state of eruption, but the

numerous, and at times, disastrous earthquakes with which Chile is visited,

give evidence that the fires which rage within are as fierce as ever.

Valparaiso from "Deck and Port",

Rev. Walter Colton (1850)

South of Valparaiso is an elevated ridge,

which gradually slopes from the upper portion of the town to a distance of two

or three miles; its undulating outline terminates the view in that direction.

There are no trees in or around Valparaiso of any size; the hillsides are

covered with low bushes thinly scattered, and the dark red soil contrasting

with the green patches of verdure, the whole mingling with the blue sky, in the

distance, add still more to the singularity of this place. The vegetation, however,

has lost that green and lively hue which it wore when I first came here, but

the winter rains will restore it to its primitive beauty and render that

season, so I am informed, by far the most delightful portion of the year.

Although I have said [that] the buildings here cannot lay any great claim to

architectural elegance, yet there are exceptions; the post office and some of

the private residences on the Plaza Victoria would do credit to any city.

The walls of the houses are built of immense thickness to resist

the shock of earthquakes. The necessity of this was made very apparent to me a

few evenings after my arrival here by a heavy earthquake. It was the first I

had ever felt. I was in the second story of a building at the time and the

first intimation I had was a deep rumbling sound like the roll of thunder when

heard far off at sea; I instinctively knew what it was and started for the

stairway instanter, but before I reached it I thought the granite foundations

of the globe were breaking up; the surface of the earth seemed to rise in

mid-air as the mighty wave of lava rolled beneath our feet. I descended the

stairs with difficulty, and when I got into the Plaza del Orden it was nearly

full of people, half of whom were on their knees, crossing themselves in a

manner the most devout. The yelping and howling of innumerable dogs, with which

the city abounds, made the scene eminently ludicrous, and notwithstanding the

terror depicted on the faces of those around me, I could not refrain from

laughing. Fortunately it was not succeeded by a second shock, which is usually

the case, as a heap of ruins would have been the result. The earth was

tremulous and gave evidence of internal commotion for the three following

weeks.

The population of

the city is variously estimated at from forty to eighty thousand inhabitants,

but the latter number is nearest the truth. The better class of Chileans dress

remarkably well, while the peons all

wear the everlasting "poncho."

The favorite dress of the women is black, than which none is more appropriate,

for it contrasts finely with their handsome black eyes and the clear olive of

their complexion. They invariably wear a mantle, which is worn in a manner

peculiarly graceful; sometimes this mantle is used for the double purpose of a

masque, the face being entirely covered, with the exception of a small portion

about the eyes, and in this they strikingly remind me of that custom which used

to render so famous the women of Lima. At an early hour every Sunday morning

one will see the SeĖoritas wending their way to the different churches, clad in

this costume which has been handed down to them by their Spanish ancestors.

With regard to the social life of the natives I cannot say much, for I know but

little as yet; the influx of foreigners, however, and those of the worst sort,

since the discovery of gold in California, has changed the manner of the people

from what it was twenty years ago, and the primitive simplicity which

characterized the inhabitants of Valparaiso in the days of Capt. Basil Hall[6]

is sadly on the wane.

They have a peculiar custom here of burying the dead at night,

for no funeral procession is ever seen in the day time. There is something to

my mind very impressive about this. The quiet stillness which reigns around at

that hour, unbroken save by the measured tread of the hearse bearers or the

voice of some distant watchman, as he cries the hour of night, awakens a deeper

reflection than one is apt to have in the bustle of noonday. The Pantheon or

cemetery where the higher class of Chilenos are buried — for the peons are thrown into a common pit —

although of small size, is the neatest place of the kind I ever saw. It looks

more like a flower garden than a city of the dead.

I will make a few

remarks about the climate and then bring this wandering letter to a close. The

climate of Chili is probably unsurpassed for salubrity. The mountainous, arid,

rocky character of the country and entire absence of all rank vegetation

accounts for this in a great measure. During the five months I have been here

there has been but one rain, and two or three months more will elapse before

the rainy season sets in. Everything as a consequence is dry and parched up and

a strong wind coming in nearly every afternoon here in Valparaiso, fills the

air with clouds of dust and makes it somewhat disagreeable to be in the streets

at that time. The temperature of the air seldom exceeds 80 of Fahrenheit, and

so dry and pure is the air that even in the warmest season one does not

experience the least inconvenience from heat. Sometimes the mornings are

cloudy, or very seldom a light fog will come in from the Ocean; but, as a

general thing, the sun rises clear and cloudless above the flashing snows of

the Cordilleras; and long after his broad red disk has dipped behind the

Pacific's wave, and the nearer coast range are wrapped in the purple line of evening

gloom, the snow fields of Aconcagua are flushed with his ruddy glow.

g

LETTER

"VII"

The "Vale of Paradise"—Long dry season—The

Festival of Semana Santa[7]—Visit

to the church of St. Augustin and the Cathedral of La Matriz after

night—The lovely Chileans—Praying Peons—Grand Procession on

the night of Viernes Santo[8]—Incidents

of the same, &c., &c.

Valparaiso, Chile, S.A., April 14th 1857.

The sight of land to those who have long

been on the ocean is always hailed with rapture, and the most barren island

assumes a beauty and a grace that the landsman can scarcely realize. It is

probably for this reason that the early Spanish navigators named this place "Valparaiso,"

or the "Vale of Paradise," a name, says Capt. Hall, "that its present appearance by no

means justifies."[9]

I cannot agree altogether with the good Captain, who wrote more than thirty

years ago, in his opinion; an opinion that even the humorous Englishman was

disposed to recall, when he had climbed the mountain south of here, and looked

from a height of nearly two thousand feet, upon the vast scene which was spread

below and around him.

There has been no rain in this part of Chile

since last September, and I have quite forgotten how a rain storm looks. The

season, within the last few weeks, has changed materially; and the strong dry

winds which occasionally prevailed during the summer months do not disturb us

now with their clouds of dust and sand. Vast masses of clouds roll in from

seaward every morning and plainly indicate that a "norther" will soon

sweep over the Bay. When the bright sunlight, during the day, disperses those

clouds among the valleys, and their white fleecy folds half envelope the lofty

mountains, I am reminded of the Bay of Rio.

Last week was "Semana Santa" or Saint Week. At ten o'clock on the morning of

the 9th, all business was discontinued, not even a carriage was allowed to run

through the streets. The Chilean vessels in the Bay "cock billed"

their yards, and lowered their flags to half mast in commemoration of this

solemn event. When night came the streets were filled with women and peons, hurrying to and from the

different churches. The first church I visited was that of St. Augustin,

situated on the Plaza Victoria. This building is about one hundred feet in

length, and when finished will present quite an imposing appearance. The roof

is supported by two rows of Doric columns between which at regular intervals,

on the night in question, were suspended chandeliers, while the Altar was

splendidly illuminated with a pyramid of flashing lights which pained the eye

to gaze upon. The central space between the columns was occupied by women

kneeling on small mats and gazing intently on some image while they repeated

their prayers. Dark skinned peons,

whose high cheek bones gave strong evidence of their close relationship to the

Indian race, were scattered around in different directions, devoutly engaged in

prayer. An image of the Virgin Mary with the Child Jesus received a large share

of the worship. It was erected on a stand close to one of the columns and robed

in a rich mantle, the hem of which every good Catholic kissed previous to their

exit. Quite a number went through with the ceremony in a hurried and, I thought,

irreverent manner, but the earnestness of a majority was not to be questioned.

I saw one woman whose care-worn face indicated the hardships she had endured,

kneel upon the floor in front of the image, repeat a short prayer, then bow her

head and kiss the floor in adoration of the Shrine. No one could doubt her

sincerity. I went close to the Altar where an image of our Savior was fastened

to the cross, and a large crowd were gathered around taking their turn in

kissing the feet. While I was leaning against one of the columns, two Chileans

came and knelt down close by my side; they were not only handsome but their

faces were irradiated with that mild and gentle beauty that Religion alone can

give to woman. I never witnessed such calm devotion, as was theirs, in a Protestant

church, and when I presently left the building it was with the impression that

there must be something remarkable, if not much that was good, in a religion

which so fascinated the mind: a fascination whose influence I felt myself.

I next wended my way to the Cathedral of La

Matriz. It was nearly full of people. The Altar was more brilliantly

illuminated than that of St. Augustin; the intervals between the burning tapers

were filled up with bright colored glasses of various hues and vases of rich

flowers. Two soldiers in full uniform stood within the recess and kept guard on

either side of the Altar. There also was an image of Christ nailed to the

cross. I crowded my way up to the Altar and stepping in between the two rows of

columns— for the style of construction is similar to that of St.

Augustin— and looking toward the principal entrance, a sea of upturned

faces met my gaze. They were all women and without an exception dressed in

black. From their numerous lips there went up the busy hum of prayers, to that

Being before whom in different form but with undivided faith, we all bow and

worship. When I went out of the Cathedral I was saluted by a crowd of beggars,

to whose numerous petitions I paid but little attention.

The Cathedral of La Matriz — by no means a fine-looking

building externally — is considerably elevated above the houses in the

front of it; and over their tile-covered roofs I could see the lofty spars of

the shipping in the bay, and the shimmering light of the full orbed moon, as

her rays played upon the dimpled surface of the water. In spite of the night

and the dim haze with which the air was filled I could see, though forty miles

away, the Coast Range of mountains. During the evening I saw numerous parties

of peons, with bared heads,

perambulating the streets and praying in chorus. They would walk quite a

distance in silence, and then, as it were with one voice, repeat some passage

of a prayer. The sound of thirty or forty voices at once, breaking upon the

still night air, was very singular.

There was a great procession the next night. It was about seven

o'clock in the evening when I sallied out from the "Hotel del Orden;"

the night was clear and beautiful, as it nearly always is in this highly

favored clime, and the moon, which had just risen above the mountains in the

interior, shed a mild radiance upon every object, that acted like the invisible

charm of an enchanter's wand. I passed through the Calle San Juan de Dios, the

Plaza Victoria and then into Calle Victoria, or Victoria street. Upon either

side of this street numbers of people were waiting for the procession to pass,

but I pressed on until I met the procession, when the living tide of humanity

forced me to halt. First in order, borne upon a stand erected for the purpose,

was a figure of the Virgin Mary. At a considerable distance behind this,

resting on a white bier, was the supposed body of Christ; about an equal

distance in the rear, on a large canopied platform, was the figure of some

saint, surrounded by six beautiful little girls dressed in gold and silver

tissue. They were supposed angels, and well did they represent their part.

Their heads were wreathed with bright flowers, and their dark Spanish eyes flashed

as they peered from under the gilded canopy. Immediately following this was a

brass band. On either side of the musicians, and as far in advance as the image

of the Virgin Mary, was a row of men and boys bearing palms, to each of which

was attached a glass lantern of the shape of a truncated pyramid. The space

between the lantern bearers was occupied by the Padres and others who

officiated in the ceremonies. Several boys dressed in red robes, over which a

white gauze was thrown, walked in advance of the last mentioned Saint and the

six "angels," and waved censers of burning sandal wood.

I took my position in the crowd opposite to the band. As far in

either direction as I could see, it was one living, surging mass. The majority

were women; for the proportion in their favor in Valparaiso is as three to one

— so said — and I am not disposed to doubt it. How they withstood

the crowding and pressing is more than I can reasonably account for. The

balconies and windows on either side of the street were filled with spectators,

and I even saw some venturous boys on the house tops. As the procession

advanced towards the Plaza Victoria, the crowd became more compact, and shoving

and pushing seemed to be the order of the day, or rather night, among the

mischief-loving and less religious portion. In some places the sidewalk is

elevated two or three feet above the street, and in such places it appears to

be quite creditable to shove as many over the verge as possible. At one time

some boys approached too near the edge, and a great, burly peon, seeing what a fine chance for fun, began to sweep the "muchachos" from his path as with

the brand of the Destroying Angel. This created considerable disturbance, but

the shrill whistle of a vigilante

restored order and checked his operations rather quickly. When the procession

arrived at the Plaza it countermarched down the Calle Nueva, a street which

runs parallel with and close to Victoria. I thought for a few moments there

would be a general fight on the corner of the Plaza: some dandy, getting his

hat smashed, commenced a vigorous onslaught on those around him with his cane.

"ņQué es eso?" (What is that?) shouted a dozen voices, and on they

pressed to the conflict: but a number of vigilantes

were on the ground and soon quieted the belligerents.

It was a considerable time before I forced my way into the Calle

Nueva, and when I did the waving of the lanterns on the feathery palms, seen

far in advance and marking bright against the dark range of hills, presented a

magnificent perspective. The procession presently reached the church from

whence it set out, and people quietly dispersed. It was now late in the evening

and the moon was high in the cloudless heaven; far out on the bosom of the

Pacific there hung a light mist and as the surf of the bay beat softly on the

beach, I thought that the lovely beauty of the night surpassed the meridian

splendor of the day.

The simultaneous firing of cannon by the Chilean and French

men-of-war, at 10 o'clock on Saturday morning April 11th announced the

termination of "Saint Week" and business was again resumed.

g

LETTER VIII.

Quillota, Chile, S. A., May 5th, 1857.

Preparations for a

journey among the mountains of Chile.—Pleasurable emotions when fairly

among the valleys.—ViĖa del Mar.—Up the

ravine.—Quilpué.—First night in the Country.—An early Walk

and a late Breakfast.—The town of Limache.—The Railroad

Tunnel.—Valley of Quillota.—Entrance into the

Pueblo.—Curiosity of the women.

I have always had a desire to travel in South America, and

especially in that portion occupied by the Republic of Chile. To observe the

customs and manners of the Spanish American, of whom the Chileno is undoubtedly

the best type, and, still greater incentive, to view the magnificent scenery

with which this country abounds. Chile is a land unhackneyed by travelers;

there are no guide-books to tell the wanderer of every stream, mountain, or

gold mine, there is to be seen; and, if I except the random notes of Capt.

Hall, the written information I have obtained of this country has been scanty

indeed. I shall give you my immediate impressions of whatever I may see,

transcribing my 'Wanderings," almost literally from my Journal.

The 2nd day of May was of unparalleled and cloudless serenity,

and I watched the lingering sunlight on the Bell of Quillota, (pronounced

key-lee-o-tah) and the wintry head of Aconcagua with more than ordinary

interest. It was a late hour before my knapsack was packed to suit me, for

numerous were the articles contained within its narrow limits, but when I came

to test the weight, I found it too heavy for comfort, and was obliged, though

with regret, to take out my telescope. I was prepared for the journey, and lay

down to rest, but not to sleep, for my thoughts were busy with the future. I

heard the crowing of cocks long before day, and fell into a slight doze about

three o'clock, but the echoes of the morning gun roused me, and while the stars

were still shining in the early gray of morn, I arose, dressed, shook hands

with my good hearted roommate, shouldered my knapsack, and started "a pie".

Early as the hour was, there were many people in the streets.

Before the sun was up, I was out of the suburb of Almendral. The morning was

nearly clear; there were some cumulous clouds in the east, and out on the Ocean

some small fog banks. The air was still, and the surface of the Bay was ruffled

only by the slightest "cat's paws." The rain which fell a few days

previous had laid the dust, and when I was fairly among the valleys, and heard

the twittering of birds, and smelled the fresh green earth banks, I was thrilled

with life I never felt before; I feared that it could not last long. The road

was very winding, and after two leagues were traversed I came to the little

village of ViĖa del Mar. There are but few houses, and one street, on one side

of which is an adobe wall that forms part of an enclosure to a large field. The

valley is of considerable width here, and through it a broad swampy stream

makes its way into an arm of the sea. The railroad runs up the valley, and

instead of taking the road to Quillota, I followed the track. The valley

gradually narrowed for a league, when the mountains nearly come together. Up

one of the ravines that put down into the valley, I saw my first Chilean

palm— it bears a striking resemblance to the cabbage palm. They do not

grow to a great height, but have a large trunk; I ate my dinner in the shade of

one two feet in diameter. Four or five miles from ViĖa del Mar, the road

pursues, for a short distance, a northerly direction; it then turns to the

east, and close to the bend were several thatched huts, with gangs of natives

engaged in various games. The physical appearance of the valley changed from

this point materially; the steep precipitous character disappeared, giving way

to more gentle slopes, and when I had ascended a moderate elevation I saw

before me the higher Costeros, and a short reach of the snowy Cordilleras.

Feeling quite fatigued with my walking, I stopped in at a

roadside house to procure a drink and a little rest. I was invited to take a

seat under a rustic porch; a large bunch of purple grapes were placed before

me. I remained here an hour, and when I got up to leave I gave an old woman who

wished me a "lucky journey," some cigaritos.

She did not fail to tell me that I would certainly be robbed if I traveled

alone among the mountains. Two miles further over, a road with a brush fence on

one side, and on the other an occasional house, out of which snarling curs

barked furiously, brought me to the little village of Quilpué. I passed through

the village without stopping, and came out upon a barren plain, which was

slightly undulating. On the left, at a distance of half a mile, was the

railroad. Trees, twenty or thirty feet in height and of a dark green bushy

appearance, were scattered along the watercourse. A mile or two from Quilpué

was another collection of houses. In some of these houses they were playing the

guitar and dancing, others again were surrounded by drunken peons. It was nearly night when I

stopped at a wayside house and asked for permission to stay within, which was

readily granted. There were two elderly women, and one old, and another middle-aged

man, and these with two girls composed the family. The old man's mind was

impaired, I presume, for while he was talking to me in an incoherent manner, the

younger one whispered to me, "el no

comprende nada" (he understands nothing.)

The air grew very

cool after sunset. A brazier of coals [charcoal,

Ed.] was brought into the large rooms and I went in and watched one of the seĖoras cook the supper. For drink, I

had mate and a small piece of bread

to eat with it, but the supply did not equal the demand. An hour or two

afterward I partook of a dessert consisting of a large bowl of milk and harina - flour made from parched wheat,

ground between two stones. A bed was prepared for me in another part of the

building, on the dirt floor, and I had for a covering a single poncho that did not keep me warm. The

room was a kind of granary, and nearly filled with wheat sacks. The walls of the

building were nothing more than sticks woven together and plastered with mud on

the outside. The roof was covered with long oat straw, and when I peered out

from under my covering in the morning the light streamed through numerous

crevices in the walls. I went out and found the air cool and chilly. A fog was

coming up the valley, and the sides of the mountains were soon shrouded in the

mist. The old man was lying outside of the building, on a rug, and covered up

with his poncho. The young man shook

hands with me, and asked me how I had passed the night. I bade him 'adios' and picking up my handkerchief

took the road.

The sunlight in a few minutes gladdened the mountains and

valleys with his beams, and the fog quickly disappeared. The road pursued an

easterly direction, up a small valley that diverged from the larger one. In the

course of a mile and a half the ravines disappeared and I commenced ascending a

gorge in the mountains; when I had attained the highest part of the

"Sierra de la Campana," another rough and apparently higher mountain

stood before me. I descended into another valley, and inquired at three or four

houses for something to eat, but I met with ill success at first. I presently

came up to a party of men who told me that I could procure something in a rude

hut close by. A little girl at the same moment brought out a glass, of what I

took to be water. One of the men took it from her hand presented it to me to

drink. As I was thirsty I did not discover my mistake until I had taken two or

three swallows; when I found myself almost choked with aguardiente, the most fiery of liquors. A hearty laugh was raised

at my expense. I walked into the house and asked a woman for a cazuela. She took a pot off of the fire

and poured the contents into a large flat dish. It consisted of mutton and

potatoes boiled up together. The dish was set on a low stool, and the drunken

crowd and myself gathered around, each one having a spoon. The company were

quite happy, and talked and laughed more than considerable. When the victuals

were all devoured, I was only half satisfied, and at this juncture one of the

tipsy desired me to treat [perhaps, to stand a drink, Ed.], but my comprehension grew dull very suddenly, and seeing how

things might turn, I paid the woman a real

and vamoosed.

I descended into another valley and crossed a little brook that

bubbled over its pebbly bed, and again ascended another spur of the Costeros.

When on the summit of this, I met an old man and inquired of him how far it was

to Limache. He did not answer my question, but asked me what I wanted in

Limache. I started on again, and he said "mire," but I paid no attention to his call. In a few moments I

met a train of pack mules and asked one of the drivers: "media legua" (half a league) was

the reply. A few minutes more and I looked upon the Valley of Limache. A short

walk down an easy slope, brought me to the level plain, which is of

considerable extent and surrounded by lofty mountains. I could see the poplars

and other trees in the village of Limache. On my left and extending up to the

range of mountains, was a field enclosed with a ditch and mud wall. I crossed a

little brook in the suburbs of the town and ascended the opposite bank, and

entered one of the streets. A mud wall whitewashed was on my right, and on the

left for a short distance ran the stream I had just crossed. In its bed were

two peons making adobes. I was soon

on the plaza, and took a street that

runs to the eastward; I went some distance and then inquired for Quillota. I

was on the wrong path. I returned and took the right direction but the wrong

street; a little girl showed me the right way, and in a short time I was out of

this beautiful little village.

It is situated immediately at the base of a mountain spur, in a

rich and fertile valley, which, by proper cultivation, would be unsurpassed. I

crossed two streams of water that ran over pebbly beds, and then entered a path

which pursued a northerly direction. A league brought me to San Pedro, the

mountain through which they are boring the railroad tunnel. The tunnel will be

fifteen hundred feet in length when completed. They are cutting both ways, and

also into the bowels of the mountain by means of a shaft. I went to the shaft

and looked over, and could hear the picks striking against the granite, but

could see nothing but darkness.

I followed the new made-track to Quillota. I passed over a deep

rich soil as I could see, by the cuttings on the sides, the accumulation of

washings from the mountains around the valley. I walked between two rows of

lofty poplars, on either side of which was a green meadow for three or four

hundred yards, when I came to a high wall, the gate of which was locked, but

there was a hole through which I could creep; and thus I made my entrance into

the Pueblo of Quillota. The street in which I found myself was long and narrow,

and the houses low and mean. The people stared at me as I passed and an old

woman, more curious than the rest, invited me in her house. I seated myself and

answered the innumerable questions that she asked. She had three daughters, one

of whom brought me a plate of grapes of enormous size, while another swept the

dirt floor and then seated herself by her mother, and, leaning towards me, with

her dark dreamy eyes half shut, drank in every word I said. I ate my grapes,

and inquired for the Hotel Colombet, and in a minute more was in the Fonda

Francesca.

g

LETTER IX.

Impressions of

Quillota—Disappointment—Start to Santiago—Sierra de la

Campana—Pass the Night with my old Friends—The Wrong Path—My

Little Guide—Temblor!—Gold Mines—Hacienda de las

Palmas—Difficulty in finding the Road—Incidents in a Chile Country

House—The Highway at last—Casablanca—Ascent of the Costeros —Valley of

Curacavi.

Curacavi, Chile, S. A., May 8, 1857.

On the north side of the town of Quillota there is a high hill,

from the summit of which there is a fine view of the town and surrounding scenery.

Early on the morning of the 5th I walked around and ascended this miniature

mountain; but I found that the higher I went, the more dense became the mist,

until, when I had reached the summit, I could not see two rods in any

direction. A large cross is erected on the summit, with the inscription of "INRI"[10]

near the top, and on the cross-bar, Mission, 1849. I waited nearly an hour for

the fog to clear away, but was at last obliged to descend without an impression

of what was before me.

There are many gardens and graperies in Quillota, all enclosed

with adobe walls. In some of them I saw prickly pear trees, twelve or fifteen

feet high, laden with this delicious fruit. Water, for the purpose of

irrigation, runs in nearly every street. The houses are low, and make no

pretension to architectural elegance. There are several churches, and one of

them, from its time-worn appearance, I should take to be two hundred years old.

I returned to the Fonda, and as I was too late for the regular breakfast, I

took my meal with M. Colombet and his good-natured and inquisitive wife, who

wished to know where I was going. When I told her, she said, with surprise,

"Está muy peligroso; allá hay muchos

ladrones." (It is very dangerous; there are many robbers.)

It was nearly noon when I started on my way to the Capital,

taking the regular road to Limache, which led between two rows of poplars for

more than a league. I had scarcely left the place before the clouds rolled

away, and the "Mountain of the Bell," or Sierra de la Campana, stood

clear against the eastern sky. This mountain has a bell-shaped summit, when

viewed from Quillota. From the summit of San Pedro I took a sketch of the

valley, which compensated me in some measure for the disappointment of the morning.

The streams of water which from my elevation I could look down upon, resembled

threads of silver glittering in the sun.

The sun was hid behind the mountains, and the shades of night

were drawing around, when I was welcomed to the house where I had spent the

first night. The air was pleasantly cool on the following morning, and down the

valley there was a light fog. I walked along a blind path that led through a

ravine in a southerly direction. The path presently faded away, and I called in

at a hut to inquire the way. They gave me some directions, and after sitting a

few minutes, watching a man grinding parched wheat, I gave them some cigaritos — small paper cigars —

and went my way. But I missed the road again, and was ascending a mountain when

I heard someone crying out for me to stop. I turned around and saw one of the

boys I had just given a cigarito to,

trying to catch up with me. I stopped until he came up. He said that I was on

the wrong track, and then guided me around a hill and across a ravine, and

pointed out a path in a gorge of the mountains. While he was guiding me, I

heard a sound that filled the valleys with a roar. It seemed to come from a

northerly direction. My little guide stopped and said "Temblor !" It was an earthquake. I

passed through the mountain gorge, as directed, and saw before me a small

valley in which there were several buildings in the distance, and a good

hacienda building nearby. I passed the farmhouse on my left, and came to

another large tile-covered building, near which was a windmill of very

primitive construction. As it was near a large pit, I inferred that its power

had been used for raising dirt preparatory to gold washing. A short distance

further on was a river, now nearly dry, but a wild, rapid stream when the snow

melts off of the mountains in the spring. I walked down the bed for a

considerable distance. It is still, and has been since the days of the early

Spaniards, worked for gold. The coarse gravel was piled up in different

directions, in order to get at the fine sand wherein is the glittering metal.

There were a good many houses, or rather huts, here, and I inquired at one for

Las Palmas, for I had learned during the morning that there was such a place.

I was shown up a deep ravine, the sides of which were bare.

While ascending the bed of the ravine, the sun beamed down with a tropical

fierceness. I descended into another deep ravine which opened to the West, and

again inquired my way to the Palmas. Two children were playing on the hillside,

but they fled at my approach and hid behind a tree. As I came near the hut to

make my inquiries, I was saluted as usual by the dogs; and when I left the

whole troop rushed towards me, but not daring to make the attack, they fell

upon one another and fought like demons, the least dog in the lot gaining the

day. The ravine of which I have just spoken was beautifully wooded with dark

green trees, of from twenty to thirty feet in height. I journeyed down it for a

short distance and then turned to the South up another ravine similarly wooded,

but much narrower. The sides were lofty and steep, and I could see but a small

patch of sky above me. It was a wild romantic spot. The air was hushed and

still, and nature seemed to repose as from a mighty labor. I was oppressed with

a sense of loneliness I cannot describe. A half mile took me through the narrow

pass into a valley of considerable width, looking up which to the Eastward, I

saw a large tile covered house, enclosed with a thick adobe wall, and still

farther up the vale, I saw about a dozen tall and stately palms. It was the

Hacienda de Las Palmas. I inquired for the road to Santiago, but took the wrong

direction, and wandered for nearly a league up a narrow ravine; the farther I

went, the dimmer became the path, and more dense the chaparral; I could not see a rod in the tangled mass of brush. I

returned and took another path, but met with no better success, the second path

taking me into a more dense thicket than the first, and I was obliged, though

reluctantly to return to the Hacienda. They showed me the road, and I followed

it in a Southerly direction, for about two miles up another valley. Some of the

scenery up this valley was very beautiful. When near the summit to which it

led, and in an abrupt turn in the road, I met three Chilenos driving a lot of

oxen. A short distance farther on I passed through a gate and followed a path

which led me into a plain a league in width, upon which were feeding large

numbers of cattle. A man and boy were collecting them together. I presently

came to the enclosure where the cows, some fifty in number, were collected

together, and several girls engaged in milking them. The sun was setting and I

concluded that I would stay for the night at this place. I asked and gained

permission from an old woman who was paring potatoes for the evening meal. I

seated myself upon a low stool to observe the culinary operations, and was by

no means surprised when I saw the knife with which the potatoes were being

pared, repeatedly wiped upon a dog's back. But I have grown used to such things

among the Chilenos, and it did not spoil my appetite. The girls soon gathered

in from their work, and ranged themselves on an opposite side of the hut from

me, and when the whole family were collected together, the old woman said to me

with some pride, "Mi familia."

There were nine girls and three boys. The floor of the room was dirt, and as

uneven as the surface of the country around; a fire was built in the middle,

and, as there was no outlet for the smoke, I was nearly blinded. A large pot

sat on the burning embers, containing the supper, and entering into a

mathematical calculation as to the probable amount each one would receive, I

came to the conclusion that my portion would be very small.

In nearly every house among the peasantry I have yet visited,

there is a little table about eighteen inches high, and two feet square, upon

which to set the dish of cazuela. A

clean napkin was placed upon said little table — for this house was no

exception to the general rule — a large bowl of this favorite Chilean

dish was set thereon, and I was informed in the politest manner, that I was

sole proprietor of what was before me. I was more than delighted, for the

amount far exceeded what I had reason to expect, and my appetite was none the

worse from a hard day's journey.

When supper was over, the hut was vacated to me and the dogs,

and a vigorous attack was made by them upon the empty dishes. An old man came

to the door presently and said, "Mire,

amigo." ["Look, friend"] I arose and followed him to another

large casa, with very large openings

for doors, but the doors were not there. One man and two little boys were lying

on the pallet, spread on the smooth dirt floor, and the old woman, and one of

the girls were preparing a bed for me. I laid down and drew a thick cover for

me; when they asked me if the covering was sufficient, I replied in the

affirmative, but the seĖorita brought

a thin sheet from a corner of the room, and carefully spread it over me. The

hot victuals I had just eaten filled my whole system with a fiery glow, but

towards morning it all glowed out, and I thought I might as well have slept

under the starry dome without, for all the good the shelter afforded me. I was

up before sunrise, the air was sharp and cool, and there was a heavy frost

spread over the ground.

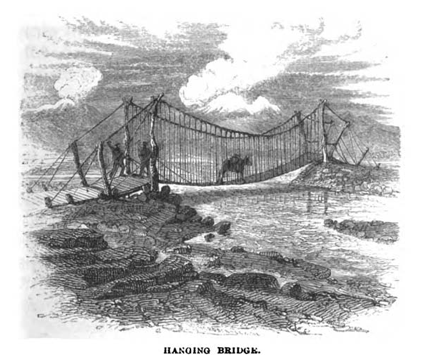

I struck down the

valley, and after going about two leagues, I saw, towards the south, a bridge,

and a row of poles placed at regular intervals. It was the highway from the

Port to Santiago. A small stream was to be crossed before I reached it, and I

was nearly mired in the bog in so doing. The road was broad, and in places

parties of peons were engaged in

repairing breaks, occasioned by the recent rains. The road presently led in

among the mountains, and a distance of four leagues brought me to an abrupt

turn, and I saw another valley of considerable extent, and the road stretching