| “There's History in every Story” |

|

|

|

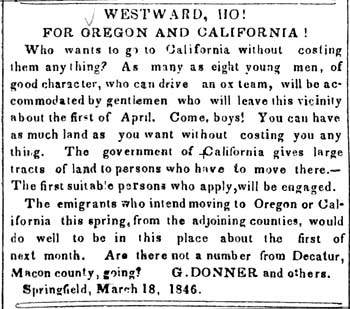

WESTWARD, HO! FOR OREGON AND CALIFORNIA ! Who wants to go to California without costing them anything? As many as eight young men, of good character, who can drive an ox team, will be accommodated by gentlemen who will leave this vicinity about the first of April. Come, boys! You can have as much land as you want without costing you any thing. The government of California gives large tracts of land to persons who have to move there.— The first suitable persons who apply, will be engaged. The emigrants who intend moving to Oregon or California this spring, from the adjoining counties, would do well to be in this place about the first of next month. Are there not a number from Decatur, Macon county, going? G. DONNER and others, Springfield, March 18, 1846. |

The wagon train that left Springfield, Illinois on April 16,

1846, was just one of dozens heading westward, year after year, with the

promise of a new life in California or Oregon.

A recruiting advertisement (see above) was placed in the local paper, announcing

the group's departure plans. All went relatively well as far as Wyoming, when

the group took an unplanned route, and ran into increasing difficulties. Slow

progress ultimately led to their becoming snowbound in the (aptly named) Sierra

Nevada, without adequate food supplies to last through the winter. There, half

of the emigrants were to die of cold and starvation. This was the notorious Donner

Party, whose horrible experiences have gone down in history.

James Reed was one of the group's organizers; he played a key role in raising

search parties and obtaining food supplies for those stranded (who included his

wife and children). The following contemporary articles, published in the Illinois

Journal, retell the story as news of events trickled in from the west; several

of them were written by Reed himself.

| jul-1846 | Letter from South Fork of the Nebraska (Reed) |

| jul-1847 | First reports of calamity |

| aug-1847 | Second report (brief) |

| sep-1847 | Names of survivors and deceased |

| sep-1847 | Journal of one of the stranded party (McKinstry) |

| dec-1847 | Abstract of journal (Reed) |

| dec-1847 | Letter from step-daughter of Reed |

| dec-1847 | Letter from Reed |

Illinois Journal, 30 July 1846

SPORTS OF THE WEST.

Tho following letter from a late citizen of this city, now on his way to Oregon, with his family, has been politely communicated to us for publication. It is dated—

South Fork of the Nebraska,

Ten Miles from the Crossings.

Tuesday, June 16, 1846.

To-day, at nooning, there passed, going to the States, seven men from Oregon, who went out last year. One of them was well acquainted with Messrs. Ide, and Caden Keys,—the latter of whom he says went to California. They met the advance Oregon caravan about 150 miles west of Fort Laramie, and counted in all for California and Oregon (excepting ours), four hundred and seventy-eight wagons. There is in ours forty wagons, which make 518 in all; and there is said to be twenty yet behind.

To-morrow we cross the river, and by our reckoning will be 200 miles from Fort Laramie, where we intend to stop and repair our wagon wheels; they are nearly all loose, and I am afraid we will have to stop sooner if there can be found wood suitable to heat the tire. There is no wood here, and our women and children are now out gathering "Buffalo chips" to burn in order to do the cooking. These "chips" burn well.

So far as I am concerned, my family affairs go on smoothly, and I have nothing to do but hunt, which I have done with great success. My first appearance on the wilds of the Nebraska as a hunter, was on the 12th inst., when I returned to camp with a splendid two year old elk, the first and only one killed by the caravan as yet. I picked the elk I killed, out of eight of the largest I ever beheld, and I do really believe there was one in the gang as large as the horse I rode.

We have had two Buffalo killed. The men that killed them are considered the best buffalo hunters on the road—perfect "stars." Knowing that Glaucus could beat any horse on the Nebraska, I came to the conclusion that as far as buffalo killing was concerned, I could beat them. Accordingly yesterday I thought to try my luck. The old buffalo hunters and as many others as they would permit to be in their company, having left the camp for a hunt, Hiram Miller, myself and two others, after due preparation, took up the line of march. Before we left, every thing in camp was talking that Mr so and so, had gone hunting, and we would have some choice buffalo meat. No one thought or spoke of the two Sucker hunters, and none but the two asked to go with us.

Going one or two miles west of the old hunters on the bluffs, and after riding about four miles, we saw a large herd of buffalo bulls. I went for choice young meat, which is the hardest to get, being fleeter and better wind.— On we went towards them as coolly and calmly as the nature of the case would permit. And now, as perfectly green as I was I had to compete with old experienced hunters, and remove the stars from their brows, which was my greatest ambition, and in order too, that they might see that a Sucker had the best horse in the company, and the best and most daring horseman in the caravan. Closing upon a gang of ten or twelve bulls, the word was given, and I was soon in their midst, but among them there was none young enough for my taste to shoot, and upon seeing a drove on my right I dashed among them, with Craddock's pistol in hand—(a fine instrument for Buffalo hunters on the plains)— selected my victim and brought him tumbling to the ground, leaving my companions far behind. Advancing a little further, the plains appeared to be one living, moving mass of bulls, cows and calves. The latter took my eye, and I again put spur to Glaucus and soon found myself among them, and for the time being defied by the bulls, who protected the cows and calves. Now I thought the time had arrived to make one desperate effort, which I did by reining short up and dashing into them at right angles. With me it was an exciting time, being in the midst of a herd of upwards of a hundred head of buffalo alone, entirely out of sight of my companions. At last I succeeded in separating a calf from the drove, but soon there accompanied him three huge bulls, and in a few minutes I separated two of them. Now having a bull that would weigh about 1200 lbs., and a fine large calf at full speed, I endeavored to part the calf from the bull without giving him Paddy's hint, but could not accomplish it. When I would rein to the right where the calf was, the bull would immediately put himself between us. Finding I could not separate on decent terms, I gave him one of Craddock's, which sent him reeling. And now for the calf without pistol being loaded. Time now was important—and I had to run up and down hill at full speed loading one of my pistols. At last I loaded, and soon the chase ended.— Now I had two dead and a third mortally wounded and dying.

After I had disposed of my calf, I rode to a small mound a short distance off to see if Hiram and the others were in sight. I sat down, and while sitting I counted 597 buffalo within sight. After a while Miller and one of the others came up. We then got some water from a pond near by, which was thick with mud from the buffaloes tramping in it. Resting awhile the boys then wanted to kill a buffalo themselves. I pointed out to them a few old bulls about a mile distant. It was understood that I was not to join in the chase, and after accompanying the boys to the heights where I could witness the sport, they put out at full speed. They soon singled out a large bull, and I do not recollect of ever having laughed more than I did at the hunt the boys made. Their horses would chase well at a proper distance from the bull. As they approached he would come to a stand and turn for battle. The horses would then come to a halt, at a distance between the boys and the buffalo of about 40 yards. They would thus fire away at him, but to no effect. Seeing that they were getting tired of the sport and the bull again going away, I rode up and got permission to stop him if I could. I put spurs to Glaucus and after him I went at full speed. As I approached the bull turned around to the charge. Falling back and dashing towards him with a continued yell at the top of my lungs I got near enough to let drive one of my pistols. The ball took effect, having entered behind the shoulders and lodged in his lungs. I turned in my saddle as soon as I could to see if he had pursued me, as is often the case after being wounded. He was standing nearly in the place where he received the shot, bleeding at the nostrils, and in a few seconds dropped dead. I alighted and looped my bridle over one of his horns. This Glaucus objected to a little, but a few gentle words with a pat of my hand she stood quiet and smelled him until the boys came up. Their horses could not be got near him. Having rested, we commenced returning to the place where I killed the last calf. A short distance off we saw another drove of calves. Again the chase was renewed, and soon I laid out another fine calf up on the plains. Securing as much of the meat of the calves as we could carry, we took up the line of march for the camp, leaving the balance for the wolves, which are very numerous. An hour or two's ride found us safely among our friends, the acknowledged hero of the day, and the most successful buffalo hunter on the route. Glaucus was closely examined by many to-day, and pronounced the finest nag in the caravan. Mrs. R. will accompany me in my next buffalo hunt, which is to come off in a few days.

The face of the country here is very hilly, although it has the name of "plains." The weather rather warm—thermometer ranging in the middle of the day at about 90, and at night 45.

The Oregon people tell me that they have made their claims at the head of Puget Sound, and say that the late exploration has made the northeast, or British side of the Columbia, far superior to the Willamette Valley, in quality and extent of territory.

Our teams are getting on fine so far. Most of the emigrants ahead have reduced their teams. The grass is much better this year throughout the whole route than the last.

Respectfully your brother,

JAMES F. REED.

JAS. W. KEYS, Esq.

Illinois Journal, 29 July 1847

FROM CALIFORNIA.

California papers to the 6th March have been received at Boston. The political news is not important. But these papers contain most distressing accounts from a company of emigrants—among whom were the emigrants from Illinois. They tried a new route across the mountains, and fearing a failure of provisions, Mr. Reed and some others, proceeded in advance of the company, leaving them on the north of the mountains in camp, (150 miles from the nearest California settlements,) to Sutter's fort, obtained provisions, reached Bear river, could not cross it for the flood. Cached his provisions, returned to the fort for more provisions and an additional force, started for the mountains, but no information had been received of the success of the undertaking. A party of fifteen left the camp on the middle of November, and of these nine died of starvation on the route; and the remainder, six females, arrived at the settlements in great distress. /*/ There was a rumor that a party of twenty-four subsequently left the camp, and all were lost in a tremendous snow storm upon the mountains. It was said that the party in the camp had provisions enough to last them to the middle of February, by which time it was hoped they would be relieved. The names of the dead, who belonged to the first party which left the camp are—Patrick Dolan, William Stanton, Wm. Fosdick, L. Murphy, Graves, two young men whose names are not given, and two Indians. There were some sixty left in camp, most of them women and children. The next news from California will be looked for with painful interest.

* Another account state that two of the men and all the women survived.

Illinois Journal, 12 August 1847

Late From Oregon & California,

The St. Louis Republican of yesterday, announces the arrival of Messrs. Shaw and Bolder, direct from Oregon. They left on the 7th of May, and were 83 days on the trip. Nineteen person came with them. They passed the Pawnees with little trouble, gave them some tobacco, clothes, &c.— They met the Oregon and California emigrants, who were getting along well—being 25 days ahead of the usual time occupied by emigrants. They met Davidson's company at Big Sandy.

These gentlemen confirm the accounts of the sufferings of the company of California emigrants, but we are glad to learn that Reed's family and the connexions of the Donner's reached Sutter's settlement after much suffering. Mrs. George Donner was dead. Donner had been robbed of his money; which had been subsequently recovered.

Illinois Journal, 2 September 1847

FROM CALIFORNIA.

The Editors of the St. Louis Republican have received files of the California papers to the 5th of June. They contain a good many matters of interest to this country. [...] All the papers referred to, give painful details of the sufferings of the emigrants in the mountains. We shall give a journal of one of the sufferers—containing a most awful narrative of events—in our next paper. We annex a statement of the survivors of the company, as well as of those who perished in the mountains.

ARRIVED IN CALIFORNIA.

William Graves, Sarah Fosdick, Mary Graves, Ellen Graves, Elizabeth Graves, Loithy Donner, Lean Donner, Francis Donner, Georgianna Donner, Eliza Donner, John Battiste, Solomon Hook, Geo. Donner, Jr., Mary Donner, Mrs. W. Woolfinger, Lewis Kiesburg, Mrs. Kiesburg, William Foster, Sarah Foster, Simon Murphy, Mary Murphy, Harriet Pike, Miomin Pike, Wm. Eddy, Patrick Breen, Margeret Breen, John Breen, Edward Breen, Patrick Breen, Jr., Simon Breen, James Breen, Peter Breen, Isabella Breen, Eliza Williams, James F. Reed, Mrs. Reed, Virginia Reed, Martha Reed, Thomas Reed, Noah James.

PERISHED IN THE MOUNTAINS.

C. T. Stanton, Mr. Graves, Mrs. Graves, Mr. J. Fosdick, Franklin Graves, John Denton, Geo. Donner, Sen., Mrs. Donner, Chas. Berger, Joseph Rhinehart, Jacob Donner, Betsy Donner, Wm. Johnson, Isaac Donner, Lewis Donner, Samuel Donner, Sam'l Shoemaker, James Smith, Balis Williams, Bertha Kiesburg (child), Lewis Kiesburg, Mrs. Murphy, Lemuel Murphy, Geo. Foster, Catharine Pike, Ellen Eddy, Patrick Dolan, Augustus Spitzer, Milton Elliot, Lantron Murphy, Mr. Pike, Antonio, (New Mexican,) Lewis, (Sutter's Indian.) Salvadore, (Sutter's Indian.) Margaret Eddy.

Illinois Journal, 16 September 1847

THRILLING JOURNAL.

Copy of a Journal kept by a Suffering Emigrant, on the California Mountains, from October 31st, 1846, to March 1st, 1847.

TRUCKEY'S LAKE, Nov. 20, 1846.

Came to this place on the 31st of last month; went into the Pass, the snow so deep we were unable to find the road, and when within three miles from the summit, turned back to this shanty, on Truckey's Lake. Stanton came up one day after we arrived here; we again took our teams and wagons and made another unsuccessful attempt to cross, in company with Stanton; we returned to the shanty, it continuing to snow all the time. We now have killed most part of our cattle, having to remain here until next spring, and live on lean beef, without bread or salt. It snowed during the space of eight days, with little intermission, after our arrival, though now clear and pleasant, freezing at night; the snow nearly gone from the valleys.

Nov. 21—Fine morning, wind N. W. ; twenty-two of our company about starting to cross the mountains this day, including Stanton and his Indians.

Nov. 22—Froze hard last night; fine and clear to-day; no account from those on the mountains.

Nov. 23—Same weather, wind west; the expedition across the mountains returned after an unsuccessful attempt.

Nov. 25—Cloudy ; looks like the eve of a snow storm; our mountaineers are to make another trial to-morrow, if fair; froze hard last night.

Nov. 26—Began to snow last evening; now rains or sleets; the party do not start to-day.

Nov. 29—Still snowing; now about three feet deep; wind west; killed my last oxen to-day; gave another yoke to Foster; wood hard to be got.

Nov. 30—Snowing fast; looks as likely to continue as when it commenced; no living thing without wings can get about.

Dec. 1—Still snowing; wind west; snow about six or six and a half feet deep; very difficult to get wood, and we are completely housed up; our cattle all killed but two or three, and these, with the horses and Stanton's mules, all supposed to be lost in the snow; no hopes of finding them alive.

Dec. 3—Ceases snowing; cloudy all day; warm enough to thaw.

Dec. 4—Beautiful sunshine, thawing a little; looks delightful after the long storm; snow seven or eight feet deep.

Dec. 5—The morning fine and clear; Stanton and Graves manufacturing snow-shoes for another mountain scrabble; no account of mules.

Dec. 8—Fine weather; froze hard last night; wind south-west; hard work to find wood sufficient to keep us warm, or cook our beef.

Dec. 9—Commenced snowing about eleven o clock; wind north-west; took in Spitzer yesterday, so weak that he cannot rise without help, caused by starvation. Some have a scant supply of beef; Stanton trying to get some for himself and Indians; not likely to get much.

Dec. 10—Snowed fast all night, with heavy squalls wind; continues to snow; now about seven feet in depth.

Dec. 14—Snows faster than any previous day; Stanton and Graves, with several others, making preparations to cross the mountains on snow-shoes; snow eight feet on a level.

Dec. 16—Fair and pleasant; froze hard last night; the company started on snow-shoes to cross the mountains; wind south-east.

Dec. 17—Pleasant; Wm. Murphy returned from the mountain party last evening; Balis Williams died night before last; Milton and Noah started for Donners' eight days ago, not returned yet; think they are lost in the snow.

Dec. 19—Snowed last night, thawing to-day; wind north-west, a little singular for a thaw.

Dec. 20—Clear and pleasant; Mrs. Reed here; no account from Milton yet; Charles Burger set out for Donners'; turned back unable to proceed; tough times, but not discouraged; our hopes are in God; Amen.

Dec. 21—Milton got back last night from Donner's camp; sad new ; Jacob Donner, Samuel Shoemaker, Rhinehart and Smith are dead; the rest of them in a low situation; snowed all night, with a strong south-west wind.

Dec. 23—Clear to-day; Milton took some of his meat away; all well at their camp. Began this day to read the "Thirty days' Prayers;" Almighty God grant the requests of unworthy sinners !

Dec. 24—Rained all night, and still continues; poor prospect for any kind of comfort, spiritual or temporal.

Dec. 25—Began to snow yesterday, snowed all night and snows yet, rapidly; extremely difficult to find wood; offered our prayers to God this, Christmas, morning; the prospect is appalling, but we trust in him.

Dec. 27—Cleared off yesterday; continues clear; snow nine feet deep; wood growing scarcer; a tree, when felled, sinks into the snow, and is hard to be got at.

Dec. 30—Fine, clear morning; froze hard last night; Charles Barger died last evening about 10 o'clock.

Dec. 31—Last of the year; may we, with the help of God, spend the coming year better than we have the past, which we propose to do if it be the will of the Almighty to deliver us from our present dreadful situation; Amen. Morning fair, but cloudy; wind east-by-south; looks like another snow storm; snowstorms are dreadful to us; the snow at present is very deep.

Jan. 1, 1847—We pray the God of mercy to deliver us from our present calamity, if it be His holy will. Commenced snowing last night, and snows a little yet; provisions getting scant; dug up a hide from under the snow yesterday; have not commenced on it yet.

Jan. 3—Fair during the day; freezing at night; Mrs. Reed talks of crossing the mountains with her children.

Jan. 4—Fine morning, looks like spring; Mrs. Reed and Virginia, Milton Elliot and Eliza Williams started a short time ago, with the hope of crossing the mountain; left the children here; it was difficult for Mrs. Reed to part with them.

Jan. 6—Eliza came back from the mountains yesterday evening, not able to proceed; the others kept ahead.

Jan. 8—Very cold this morning; Mrs. Reed and others came back, could not find their way, on the other side of the mountains; they have nothing but hides to live on.

Jan. 10—Began to snow last night; still continues; wind west-north-west.

Jan. 13—Snowing fast; snow higher than the shanty; it must be thirteen feet deep; cannot get wood this morning; it is a dreadful sight for us to look upon.

Jan. 14—Cleared off yesterday; the sun shining brilliantly renovates our spirits; praise be to the God of Heaven.

Jan. 15—Clear day again; wind north-west; Mrs. Murphy blind; Lanthron not able to get wood; has but one axe between him and Kiesburg; it looks like another storm; expecting some account from Sutter's soon.

Jan. 17—Eliza Williams came here this morning; Lanthron crazy last night; provisions scarce; hides our main subsistence; may the Almighty send us help.

Jan. 21—Fine morning; John Battise and Mr. Denton came this morning, with Eliza: she will not eat hides; Mrs. ____ sent her back to live or die on them.

Jan. 22—Began to snow after sunrise; likely to continue; wind north.

Jan . 23—Blew hard and snowed all night, the most severe storm we have experienced this winter; wind west.

Jan. 26—Cleared up yesterday; to-day fine and pleasant, wind south; in hopes we are done with snowstorms; those who went to Sutter's not yet returned: provisions getting scant; people growing weak; living on small allowance of hides.

Jan. 28—Commenced snowing yesterday—still continues to day. Lewis (Sutter's Indian,) died three days ago—food growing scarcer—don't have have enough to cook our hides.

Jan. 30—Fair and pleasant; wind west; thawing in the sun; John and Edward Breen went to Graves' this morning ; the ____ seized on Mrs. ____ goods until they would be paid; they also took the hides which herself and family subsisted upon.—She regained two pieces only, the balance they have taken. You may judge from this what our fare is in camp; there is nothing to be had by hunting, yet perhaps there soon will be.

Jan. 31—The sun does not shine out brilliant this morning; froze hard last night; wind north-west. Lantron Murphy died last night about 1 o'clock; Mrs. Reed went to Graves' this morning to look after goods.

Feb. 5—Snowed hard until 12 o clock last night; many uneasy for fear we shall all perish with hunger; we have but little meat left, and only three hides; Mrs. Reed has nothing but one hide, and that is on Graves' house; Milton lives there, and likely will keep that: Eddy's child died last night.

Feb. 6—It snowed faster last night and to-day than it has done this winter before; still continues without intermission; wind south-west; Murphy's folks and Kiesburg say they cannot eat hides; I wish we had enough of them; Mrs. Eddy is very weak.

Feb. 7—Ceased to snow at last; to-day it is quite pleasant; McCutcheon's child died on the 2d of this month.

Feb. 8—Fine clear morning; Spitzer died last night; we will bury him in the snow. Mrs. Eddy died on the night of the 7th.

Feb. 9—Mr. Pike's child all but dead. Milton is at Murphy's not able to get out of bed; Kiesburg never gets up; he says he is not able; Mrs. Eddy and child were buried to-day; wind south-east.

Feb. 10—Beautiful morning; thawing in the sun; Milton Elliot died last night at Murphy's shanty; Mrs. Reed went there this morning to see after his effects. J. Denton trying to borrow meat for Graves; had none to give; they had nothing but hides; all are entirely out of meat; but a little we have; our hides are nearly all eat up, with God's help spring will soon smile upon us.

Feb. 12—Warm, thawy morning.

Feb. 14—Fine morning, but cold. Buried Milton in the snow. John Denton not well.

Feb. 15—Morning cloudy until 9 o'clock then cleared off warm. Mrs. ____ refused to give Mrs. ____ any hides. Put Sutter's pack-hides on her shanty and would not let her have them.

Feb. 16—Commenced to rain last evening, and turned to snow during the night, and continued until morning; weather changeable, sunshine, then light showers of hail, and wind at times. We all feel very unwell; the snow is not getting much less at present.

Feb. 19—Froze hard last night. Seven men arrived from California yesterday evening with provisions, but left the greater part on the way. Today it is clear and warm for this region; some of the men have gone to Donners' camp; they will start back on Monday.

Feb. 22—The Californians started this morning, twenty-four in number, some in a very weak state; Mrs. Kiesburg started with them, and left Kiesburg here, unable to go. Buried Pike's child this morning in the snow; it died two days ago.

Feb. 23—Froze hard last night; to-day pleasant and thawy—has the appearance of spring, all but the deep snow; wind south south-east. Shot a dog to-day, and dressed his flesh.

Feb. 25—To-day Mrs. Murphy says the wolves are about to dig up the dead bodies around her shanty, and the nights are to cold too watch them, but we hear them howl.

Feb . 26—Hungry times in camp; plenty of hides, but the folks won't eat them; we eat them with tolerable good appetite, thanks be to the Almighty God. Mrs. Murphy said here yesterday, that she thought she would commence on Milton and eat him; I do not think she has done so yet; it is distressing. The Donners told the California folks, four days ago, that they would commence on the dead people, if they did not succeed that day or the next in finding their cattle, then ten or twelve feet under the snow, and did not know the spot or any where near it; they have done it ere this.

Feb. 18—One solitary Indian passed by yesterday; came from the lake; had a heavy pack on his back; gave me five or six roots resembling onions in shape; tasted some, like a sweet potato, full of tough little fibres.

March 1—Ten men arrived this morning from Bear Valley, with provisions. We are to start in two or three days, and cache our goods here.—They say the snow will remain until June.

The above mentioned ten men started for the valley with seventeen of the sufferers; they traveled fifteen miles and a severe snow storm came on; they left fourteen of the emigrants, the writer of the above journal and his family, and succeeded in getting in but three children. Lieut. Woodworth immediately went to their assistance, but before he reached them they had eaten three of their number, who had died from hunger and fatigue; the remainder Lieut. Woodworth's party brought in. April, 1847, the last member of the party was brought to Capt. Sutter's Fort. It is utterly impossible to give any description of the sufferings of the company. Your readers can form some idea of them by perusing the above diary.

Yours, &c.,

GEORGE MCKINSTRY, JR.

Fort Sacramento,

April 27, 1847.

Illinois Journal, 9 December 1847

NARRATIVE OF THE SUFFERINGS of a Company of Emigrants in the Mountains of California, in the winter of '46 and '7 by J. F. Reed, late of Sangamon County, Illinois.

[The following narrative was prepared for the press by Mr. J. H. MERRYMAN, from notes written by Mr. J. F. REED. We copy from the State Register,—omitting the list of those who survived and those who perished,—having published the same several week's since.]

Through the kindness of Mr. JAMES W. KEYS, Esq., we are enabled to lay before our readers an abstract of the journal of Mr. JAMES F. REED, who emigrated from this place, some two years since, to California.

He says that his misfortunes commenced on leaving Fort Bridger, which place he left on the 31st of August, 1846, in company with eighty-one others. Nothing of note occurred until the 6th of September, when they had reached within a few miles of Weaver Canyon, where they found a note from a Mr. Hastings, who was twenty miles in advance of them, with sixty wagons, saying that if they would send for him he would put them upon a new route, which would avoid the Canyon and lessen the distance to the great Salt Lake several miles. Here the company halted, and appointed three persons, who should overtake Mr. Hastings and engage him to guide them through the new route, which was promptly done. Mr. Hastings gave them directions concerning this road, and they immediately recommenced their journey. After travelling eighteen days they accomplished the distance of thirty miles, with great labor and exertion, being obliged to cut the whole road through a forest of pine and aspen. They halted upon the south end of the great Salt Lake, where they remained several days. Mr. Reed describes the water of this lake, to use his own expression, as strong enough to brine beef. Leaving this place on the 30th September, they proceeded on their way, crossing a large desert, devoid of water, on account of which they lost several of their finest cattle.—When within nine hundred miles of the California settlements they discovered that their stock of provisions was insufficient to last them until they had traveled that distance; therefore, they appointed two persons, Messrs. C. F. Stanton, of Chicago, and William McClutchem, of Clay county, Mo., who should proceed with all possible haste to Fort Sacramento, owned by Capt. Sutter, procure supplies, and return as soon as possible. They accordingly started on their errand, and although having near a thousand miles to go, they calculated that they would return in a short time. The company then proceeded, and after traveling three hundred miles, giving ample time, as they supposed, for the return of Messrs. Stanton and McClutchem, and fearing that some accident had befallen them, they determined to send another messenger. Mr. Reed was at once chosen as the most proper person for this service, and providing himself with seven days' provision, he commenced his lonesome march. Before him lay a journey of six hundred miles, which he must accomplish on foot, for although he had a horse, it was so weak that it could not carry his saddle-bags and blanket. He left the company at Mary's river. On the second day's march he overtook the Donners, who were in advance, on account of the superior condition of their cattle.—Here he was joined by Walter Herron. He found the Donners subsisting on the carcasses of some of their cattle, which had been killed by the Indians in a night attack two days previous. In company with Herron he pursued his way; the scanty supply of provisions soon gave out; along the banks of Mary's and Tucker's rivers they found a little game; after leaving the latter they saw none at all. For seven days they journeyed through that wilderness, during which time they ate but two meals, and they were made of wild onions. Fortunately, at the end of the time they reached Bear river valley, where they found a small party of emigrants, who had halted to recruit their cattle, and were awaiting the arrival of supplies from Mr. Johnson's, the first house in the California settlements, and distant from Bear river sixty miles, and to their infinite delight they also met Mr. Stanton on his return to the company. He did not recognize Mr. Reed, who suffered much from his toilsome journey. During the seven days of starvation, he had traveled successively 38, 35, 25, 30, 26, 20 and 17 miles each day.

Captain Sutter had provided Mr. Stanton with flour, dried meat, seven horses and two of his choicest Indians. Mr. Reed, not deeming the supplies sufficient for the support of the company to Bear river, determined to push on to Fort Sacramento, obtain additional aid, and meet the company at Bear River Valley, while Mr. Stanton should proceed with his supplies to their aid. On the 23d October, Mr. Reed started for Fort Sacramento, leaving Herron with the party of emigrants, he being unable to travel. After traveling one hundred miles, he reached the Fort, and was received at the gate by the generous hearted Sutter, who furnished him with large quantities of flour and meat, twenty-six horses, and a number of Indians. Here he found Mr. McClutchem, who had been left by Mr. Stanton. Mr. McC. joined Mr. R. on his return. Two days after leaving the Fort, it commenced raining; and the third day, the tops of the great California Mountains were covered with snow.—For four days they traveled in the rain, and at the end of that time reached the head of Bear River, where they found snow eighteen inches deep.— The next day's march brought them to snow thirty inches in depth. Here the Indians deserted them; and on this account, they were obliged to leave nine horses in camp. Starting with seventeen horses, they proceeded to cross the mountains. As they advanced the snow became deeper; they reached the depth of four feet, when the horses sank completely exhausted, and it was found impossible to proceed with them. Messrs. Reed and McClutchem determined to use every effort to reach their friends. Choosing the best horses, they urged them forward—but alas !—they were obliged to leave the poor animals completely buried in snow. They then attempted to pursue their journey on foot, but for the want of snow shoes, were obliged to abandon all hope of passing that huge barrier of snow, which separated them from their families; and gathering their horses together, they returned to the valley, and went from there to Mr. Johnson's, who received them in the most hospitable manner. Here they asked for information in relation to the mountains, not obtaining any but the most discouraging, they proceeded to Fort Sacramento, throwing themselves upon the generosity of the ever kind Sutter. Here he was told that it would be vain for him to attempt to reach his friends until the 1st of February, when the storms of winter should cease. But Mr. Reed was not satisfied with this, he determined to go to the Lower Californias, and seek for aid from that quarter. Arriving at the Pueblo de los Angeles, he met Lieut. R. F. Pinkney, U. S. Navy, then in command of that place. Under the patronage of this gentlemen, he became acquainted with several Americans. He stated his many misfortunes, and implored relief, but this was impossible to obtain; at that time the Californians had rebelled in strong force, and peace must be established before anything could be done for the sufferers in the mountains. Under these circumstances, Mr. Reed had but one alternative—to obtain the aid of his countrymen in that part of California he must aid them in avoiding the danger which threatened them. He, therefore, entered the service of the United States as first lieutenant of a company of Mounted Riflemen; his company numbered thirty men—"sailors, whalers and landsmen;" these were joined by twenty citizen volunteers, one company of Marines, and one piece of artillery, hauled by two yoke of oxen. With this force, they marched against the enemy, who they met (300 strong) upon Santa Clara plains, and defeated them entirely. A peace followed this decisive battle, and the army returned to San Francisco, where they were disbanded. Now the citizens turned their attention towards their suffering countrymen, who, while these events were transpiring, had reached the mountains, where they found that the snow had formed an insurmountable barrier to their further progress; they therefore, halted and built such cabins as they could. Their provisions being exhausted, they had recourse to their cattle, rendered miserable by rough usage and famine; when the meat failed, the hides were resorted to, and when they too had been devoured, then human flesh was seized by the unfortunates to preserve their lives.

A meeting was called at San Francisco, contributions were made, and the sum of $ 1,000 was raised in the city. On board the ships Portsmouth and Warren $300 was contributed by the sailors. A committee of purchases was then appointed, which repaired on board a launch, owned by Messrs. Smith and Ward, and purchased everything necessary for the relief of the sufferers. Messrs. Smith and Ward then kindly offered the use of their fine launch to convey the supplies to the mouth of Feather River; for the plan of operations was, to send all the supplies to that place, in charge of a party of men under Passed Midshipman Woodworth, while Mr. Reed should enlist a sufficient number of men, purchase horses, and proceed by land to the same point, there pack his horses with the supplies, and then go forward to the mountains. Just as they were preparing to start, a small launch belonging to Sutter, came in from Sacramento bringing the intelligence that two men and five women had arrived at Mr. Johnson's from the mountains, the survivors of a party of fifteen persons, who had started from the cabins on the east of the chain. This party had left their companions for the purpose of lessening the consumption of the provisions, and that they might send aid to them.— The sufferings of this party were truly awful. A synopsis of the journal of Wm. H. Eddy, of Belleville, will give the reader a better a idea of the hardships endured by them. He commences with

Dec. 16, 1846.—Started from the cabins, in all fifteen persons, (the names of the party were as follows: Mr. Graves, Patrick Dolen, Jay Fosdick, C. F. Stanton, Antonio, a Mexican, Lemuel Murphy, Lewis and Salvador, Indians, Wm. H. Eddy, Wm. Foster, Mrs. McClutchem, Mrs. Fosdick, Miss Mary Graves, Mrs. Foster and Mrs. Pike,) on snow shoes, for the California settlements;— traveled four miles, and arrived at the head of Truckey's lake. 17th.—Crossed the great chain. 18th.—Descended Juba creek about six miles; commenced snowing; wind blowing cold and furiously. 19th.—Storm continued; feet commenced freezing. 20th.—Left Juba; traveled four miles. 21st.— Went down the mountain in a southerly direction; provision exhausted; Stanton snow blind; he did not reach camp at night. 22d.—Remained in camp waiting for Stanton. 23d.—Cleared off; ascended a mountain for observation; still in hopes that Stanton would arrive. 24th.—Left top of mountain; proceeded down a valley three miles; storm recommenced with greater fury; extinguished fires. 25th.—Antonio and Mr. Graves died; remained in camp. 26th—Could not proceed; almost frozen; no fire. 27th.—Still in camp; no fire; Patrick Dolin died. 28th.—Storm abated; succeeded in making fire; Lemuel Murphy died. 29th.—No food for five days; a portion of the company eat human flesh. 30th.—Stripped all the flesh from three of the bodies; traveled four miles.— 31st.—Traveled six miles.

January 1, 1847. —Passed a rugged canyon. 2d.— Continued down the valley. 3d.—Mr. Fosdick became very weak; had to wait for him. 4th.—Nothing to eat. 5th.—Mr. Fosdick gave out entirely; commenced eating the strings of our snow shoes. 6th—Traveled two miles; halted on account of the illness of Mr. Fosdick; Indians left us. 7th— started on trail of Indian boys; saw deer sign;— killed one. 8th—Dried deer meat by fire; went to bottom of the mountain. 9th—Ascended large mountain; entirely out of the snow. 10th—Descended the mountain. 11th—Saw the dead bodies of the two Indian boys. 13th—Proceeded down the valley, occasional snow drifts. 14th—arrived at an Indian village; procured some acorns. And on the 17th, Mr. Eddy arrived at Johnson's, leaving the rest of the party at an Indian village.

When the news of this terrible disaster reached the citizens of San Francisco, their minds were filled with consternation. From the various rumors they heard, they could hardly hope that the remainder of the emigrants were alive. But this only added new zeal to their endeavors, and on the 7th of February, every thing being ready, Mr. Woodworth and party departed in the launch for the mouth of Feather river, while Mr. Reed proceeded to Sonoma, where he added $350 to his funds, and enlisted twelve men, who were to receive three dollars per day from the date of enlistment to the date of discharge. He also procured forty horses to transport the supplies from Feather river to the cabins. Here he received intelligence, that immediately upon the arrival of Mr. Eddy at the settlements, Messrs. Sinclair, Sutler and M'Kinstry had, upon their own responsibility, fitted out an expedition for the relief of the sufferers.— This was gratifying intelligence, indeed, and inspired Mr. Reed with new hope. After a toilsome journey, over rugged mountains and swollen streams, Mr. Reed and party reached Feather river, and to their great disappointment, found that the launch had not arrived.

As no time could be lost in waiting, Mr. Reed and Mr. McClutchem pushed on to Mr. Johnson's, distant twenty-five miles, leaving the party to follow at their leisure, while they should make preparation at Mr. Johnson's to obtain supplies, independent of the launch. Arriving at Mr. Johnson's a small hand-mill, owned by him, was put in motion, and a good quantity of flour was made. Beeves were slaughtered and the meat dried, so that when the party arrived nothing was to be done but to pack their horses. On the arrival of his men and horses, Mr. Reed was informed that Mr. Woodworth had stopped at Sutter's landing, upon the Sacramento, and was fitting out an expedition to proceed to the mountains. Leaving word with Mr. Johnson that when Mr. W. should arrive he should hasten on with all speed, he started once more towards his friends. After traveling two days they reached the snow, and at a place called Mule springs they cached their saddles and bridles, and a portion of the provisions, and every man relieving the horses of a part of their load, by placing it upon their own backs, they proceeded and traveled fifteen miles without snow shoes.

Just before reaching camp the following day, they met Messrs. Glover and Rhodes of the party fitted out by Sinclair, Sutter and McKinstry, who informed them that they had reached the cabins and found the people in the worst condition possible; that they had started for the settlements with twenty-one persons, old and young, but owing to the robbery of their cache by a vicious little animal, called Marten, their provisions had become exhausted, and that they had left the party in a starving condition several miles behind. Receiving this information, Mr. Reed immediately despatched Messrs. Ritchie and Gordon to the Mule springs to bring up the provisions cached there, and with instructions that if they should meet Mr. Woodworth to send him on with all speed, for upon him Mr. Reed greatly depended for future supplies, knowing that the quantity he had himself was insufficient for the support of the sufferers from the cabins to the settlements. Had Mr. Woodworth hastened on after receiving these advices, much suffering would have been prevented, but he relied upon his own judgment, and that judgment belonging to a man young in years and of little experience, will be appreciated by the world at its proper value, and this narrative will plainly show the error of Mr. Woodworth's course.

Mr. Reed then hastened to meet the sufferers, after, however, leaving two men in his camp to prepare provisions for the sufferers as they should arrive. He had not proceeded far when he met the advance of the party, who were dragging their emaciated forms along in the snow. The first persons he met were principally children, who were stronger, and being lighter, could travel through the snow with greater facility than the rest of the party. Provisions were immediately distributed among them, and hurried them towards the camp. But, what were the feelings of Mr. Reed when he beheld his wife and two of his children tottering towards him; their forms wasted away, and their countenances pale and haggard from the ravages of famine and cold. With what feelings did he rush towards those so dear to him whom, long ago, despair had induced him to believe had perished, and what was their joy on beholding the protecting hand that had been so long lost to them. Mrs. Reed had started from the cabins with her four children.— Hardly had she proceeded two miles when her two youngest sank beneath the fatigue and were unable to proceed. She could not leave them to die, and to return to face the miseries of the cabins again, was horrible; but sooner than leave them she determined to meet any dangers, when her little daughter said, "I will go back with Thomas. If we never see each other again, do the best you can, God will take care of us." But she could not consent to part with them, until Mr. Glover told her that Mr. Reed being a brother Mason, he felt in duty bound to exert himself to save her children; that he would return with them to the cabins, and that he would pledge his honor as a Mason to return and carry them out of the mountains as soon as he should conduct the party safely to the settlements. Relying upon his faith, she consented that they should return.

Mr. Reed seeing his wife and children somewhat invigorated by the food they had received, pushed on with his party for the cabins, in the most dreadful state of anxiety in regard to the situation of his two children. Reaching the ridge dividing Bear and Juba rivers they made a cache, and proceeding ten miles further, they encamped. Two day's after this, they saw the top of a cabin just peering above the silvery surface of the snow. As they approached it, Mr. Reed beheld his youngest daughter, sitting upon the corner of the roof, her feet resting upon the snow. Nothing could exceed the joy of each, and Mr. Reed was in raptures, when on going into the cabin he found his son alive. The family at this cabin still had a little provision left from the supplies furnished by Mr. Glover. His party immediately commenced distributing their provision among the sufferers, all of whom they found in the most deplorable condition. Among the cabins lay the fleshless bones and half eaten bodies of the victims of famine. There lay the limbs, the skulls, and the hair of the poor beings, who had died from want, and whose flesh had preserved the lives of their surviving comrades, who, shivering beneath their filthy rags, and surrounded by the remains of their unholy feast, looked more like demons than human beings. They had fallen from their high estate, though compelled by the fell hand of dire necessity. Like messengers of Heaven, did Mr. Reed and party appear in the eyes of the unfortunates. They moved about dispensing their supplies, frequently arriving in time to push from the lips of sufferers the unnatural food, which they were subsisting upon. At one cabin they found children devouring the heart and liver of their father; they were even then tearing the raw flesh with their teeth, not having the patience to cook it, and their chins and bosoms were deluged with the blood.— Another family had sent to borrow a leg from the body. This strange loan was made, but with strict injunctions not to send for more, for it could not be spared.

To Mr. Reed this was a horrid sight. Among the bones and skulls that filled the camp kettles, he saw the remains of many of an old and well-tried friend. In gazing upon this revolting picture, as it were, of sufferings of the most hideous form, he thought of the narrow escape of himself and family from the cruel fate which had overtaken his companions, which cut them down in death, almost in sight of a beautiful country, where, if they could once arrive, they could live in peace and plenty, and the very country for which they left their native home and traveled many thousand miles to reach.

Gathering together those that were able to travel, and leaving two young men and seven day's provisions with those who were unable, Mr. Reed and his men cached all their effects, and set out on their return. Every day they anxiously looked for the arrival of Mr. Woodworth's party, but each day, they were doomed to disappointment; slowly they proceeded on their toilsome way, and after travelling three day's the provisions became very scarce, he then sent three of his best men to the cache upon the ridge dividing Bear and Juba, with instructions for one to return with the contents, while the other two should proceed to the next cache, and if in the meantime they did not meet Mr. Woodworth, to return with its contents also. The three men proceeded on their errand, without one morsel of provision. The party followed slowly upon their trail, accomplishing 13 miles in that day's travel. The next day, just as they reached camp, a storm, which had lurked behind threatening clouds of darkest hue for several days, now burst upon the poor emigrants with all the fury of a tornado. The winds blew a bitter, piercing blast; the pitiless snow beat fiercely against their thinly clad and weak forms; their blood grew chill within their veins, and death, with glaring eyes, stated them in the face. All that night did the storm rage, nor did it abate in the least the whole of the next day; another night was passed in the relentless storm, and it was only by the most superhuman efforts of Mr. Reed and his men, that the lives of the party were preserved. The fire had sunk into a pit in the snow, twenty feet deep, and it required the most unceasing toil to save it from the destructive power of the snow. Another morning dawned upon the vast white blank of nature, but brought no fair weather; another night spread its sable curtain over this world of snow, and still the pitiless storm howled among the towering silver coated pines, but morning dawned, fair and bright, the wind subsided, and the frozen mist sank upon the white bosom of the mountains; but now they had the misfortune to lose one of their number —little Isaac Donner, who died of starvation, for their provision had given out when the storm first came on. When it was proposed to start once more, a portion of the party objected, and under no consideration could they be prevailed upon to leave the camp; the rest feeling bound, as long as life remained, to make every exertion to reach the settlement, proceeded on their way. Owing to the softness of the snow, their journey was very toilsome, and the air became colder until they reached camp, but they had no idea of the effect of the cold upon them until a fire was started, when reaction taking place in their limbs, their agony was intense. So severe was the pain they suffered that they forgot for a time the cravings of hunger. The next day they travelled ten miles, and the great toes of many having bursted, they could have been tracked the whole distance by their blood. They had now been four days without provision, but at this camp, to their great joy, the three men, who had been despatched to the caches, came in with a little provision, the cause of their delay was, finding the first cache had been robbed by Marten, they proceeded to the next, and the great storm coming upon them, they were obliged to wait until it abated. Invigorated by these supplies, they proceeded, and two days after they reached the camp of Mr. Woodworth, in Bear River Valley.

As soon as Mr. Reed and party reached Mr. Woodworth's camp, they urged him to proceed immediately to the relief of those who had been left on the east side of the mountains, and the party that had remained at the head of Juba valley; the former having very little provision, the latter none whatever. But Mr. Woodworth and party, when gazing upon the pale and emaciated forms of the emigrants, and saw pictured upon their countenances the evidences of most intense suffering, and looked forward to the dangers that must be surmounted before they could reach and relieve the poor emigrants, they quailed before the prospect, and refused to proceed without a pilot. A pilot was, however, needless,—because the tracks made by the snow shoes of the party which had just arrived, were amply sufficient to guide them to Juba valley, from which Juba river was a sure guide to Truckey's lake, near the cabins. Of all this Mr. Woodworth was informed, but he utterly refused to proceed without a pilot. At the end of two days, a large majority of Mr. Reed's party volunteered to go with him. They went, and on their arrival at the head of Juba valley, they found the party that Mr. Reed had left. Three persons were dead, and the survivors were subsisting on their dead bodies. After making the necessary arrangements for this party to proceed to Bear river, the relief company proceeded to the cabins, where they found that six more had died since Mr. Reed's departure. Gathering the survivors, they cached all the effects of the company, and returned to Bear valley. And now after three month's starvation, among the snow-capped mountains, the survivors of this unfortunate company, are tilling the soil, beneath the perpetual summers of the valleys of California.

Illinois Journal, 16 December 1847

DEEPLY INTERESTING LETTER.

The following letter is from a little girl, aged about twelve years, step-daughter of Mr. James F. Reed, and was one of the unfortunate company of emigrants, of whose sufferings last winter, we gave an account in our last week's paper. The artless manner in which this child details the sufferings of the party, and especially of her own family—the joyful meeting of her father after his absence of five months—can scarcely be read without a tear,—while her notice of the country, which she had reached with untold tribulation, will cause a smile. "It is a great country to marry. Eliza is to be married; and this is no joke !"

CALIFORNIA, May 16, 1847.

My Dear Cousin: I take this opportunity to write, to let you know that we are all well at present, and hope this letter may find you well.—I am going, my dear cousin, to write to you about our troubles in getting to California. We had good luck till we came to Big Sandy. There we lost our best yoke of oxen, named Riley and George, and when we came to Bridger's Fort we lost two other oxen. We then sold some of our provisions and bought a yoke of cows and a yoke of oxen. The people at Bridger's Fort persuaded us to take "Hasting's Cut-off," over the salt plain. They said it saved three hundred miles. We went that road, and we had to go through a long drive, as they said, of forty miles, without water or grass. Hastings said it was forty miles; but I think it was eighty miles. We traveled a day and night, and at noon next day father went on ahead to see if he could find water. He had not gone long before some of the cattle gave out, and we had to leave the wagons and take the cattle to water. Herren and Bayliss stayed with us, and the other boys, Milt., Elliott and James Smith, went on with the cattle to water. Father was coming back to us with water, and met the men. They were then about ten miles from water, and father said they would get to water that night, and told the boys the next day to bring the cattle back for the wagons and to bring some water. Father got to us about day-light the next morning. Walter took the horse and went on to water. We waited there till night, thinking that the boys would come, and we then thought we would start and walk to Mr. Donner's wagons that night, a distance of ten miles. We took what little water we had, and some bread, and started.

Father carried Thomas, and the rest of us walked. We got to Donner's, and they were all asleep. So we laid down on the ground; we spread one shawl down; we laid on it, and spread another over us, and then put the dogs on top—Tyler, Barney, Trailer, Tracker and little Cash. It was the coldest night you ever saw for the season. The wind blew very hard, and if it had not been for the dogs, we would have froze. As soon as it was day, we went to Mr. Donner's. He said we could not walk to the water, and if we staid we could ride in the wagons to the water. So father left us and went on to the water, to see why the boys did not bring back the cattle. When he got to the water he found but one ox and one cow, and that none of the rest had got there. Mr. Donner came up that night to the water, with his cattle and brought his wagons and all of us. We staid there a week and hunted for our cattle, but could not find them. The Indians had taken them. So some of the company took oxen and went out and brought in one wagon and cached the other and a great many other things, all but what we could put in one wagon. We had to divide our provisions with the company to get them to carry it. We got three yoke of cattle from the company, including our ox and cow; and we went on that way awhile, when we got out of provisions, and father had to go on to California for provisions.

We could not get on in the way we were fixed, and in two or three days after father left us we had to cache our wagon, and take Mr. Grave's wagon and cache some more of our things. Well, we went on that way sometime, and then we had to get into Mr. Eddy's wagon. We went on that way awhile, and then we had to cache some of our clothes, except a change or two, and put them in Mr. Brien's wagon. Thomas and James rode the two horses, and the rest of us had to walk. We went on that way awhile and came to another long drive of forty miles, between Mary's river and Truckey's river, and then we went with Mr. Donner. We had to walk all the time we were traveling. Up the Truckey river we met a man, Mr. T. C. Stanton, (and two Indians,) that we had sent on for provisions to Capt. Suter's Fort before father started. He had met father not far from Suter's Fort. He looked very bad. He had not ate but three times in seven days, and the last three days without any thing. His horse was not able to carry him. Mr. Stanton gave him a horse, and he went on. We now cached some more of our things, all but what we could pack on one mule, and started again. Martha and James rode on behind the two Indians. It was then raining in the valleys and snowing on the mountains. We went on in that way three or four days, until we came to the big mountain, or the California mountain. The snow was then about three feet deep. There were some wagons there. The owners said that they had attempted to cross but could not. Well, we thought we would try it; so we started, and they in company with us, with their wagons. The snow was then up to the mules' sides. The farther we went up, the deeper the snow got—so that the wagons could not go on. They then packed their oxen, and went on with us, carrying a child a-piece, and driving the oxen in the snow up to their waists.—The mule that Martha and the Indian was on was the best one;—so they went and broke the road, and that Indian was the pilot. We went on that way two or three miles, and the mules kept falling down in the snow, heads foremost, and the Indian said he could not find the road. We stopped and let the Indian and Mr. Stanton go on and hunt the road. They went on and found it to the top of the mountain, and came back and said they thought we could get over if it did not snow any more. But the people were all so tired by carrying their children, that they could not go over that night. So we made a fire and got something to eat, and mother spread down a buffalo robe, and we all laid down upon it, and spread something over us, and mother set up by the fire, and it snowed one foot deep on the top of the bed that night. When we got up in the morning, the snow was so deep we could not go over the mountain, and we had to go back to the cabins that were built by the emigrants three years ago, and build more cabins, and stay there all winter, as late as the 20th February, and without father.

We had not the first thing to eat. Mother made an arrangement for some cattle—giving two for one in California. The cattle were so poor that they could hardly get up when they laid down. We stopped there the 4th of November and staid till the 20th of February, and what we had to eat I can't hardly tell you, and we had Mr. Stanton and the Indians to feed. But they soon left to go over the mountains on foot, and had to come back. They then made snow shoes and started again, and a storm came, and they had again to return. It would sometime snow ten days before it would stop. They waited till it stopped snowing and then started again. I was going with them, but took sick and could not go. There were fifteen persons left in this company, and but seven got through—five women and two men. A storm came on, and they lost the road, and got out of provisions, and those that got through, had to eat them who died. Not long after they left we had eaten all our provisions and we had to put Martha at one cabin, James at another, Thomas at another, and mother and Eliza and Milt, and I, dried up what little meat we could get, and started to see if we could cross over the mountain—and we had to leave the children. O Mary ! you will think that hard—to leave them with strangers, and did not know whether we ever would see them again. We could hardly get away from them. We told them we would bring them back bread, and then they were willing to stay.—We went and were out five days in the mountains. Eliza gave out and had to go back. We went on that day, and the next day we had to lay by and make snow shoes. We went on another day, and could not find the road and had to go back. I could get along very well while I thought we were going ahead, but as soon as we had to turn back I could hardly walk. We reached the cabins, and that night there was the worst snow storm that we had the whole winter, and if we had not come back, we could not have lived through it. We had now nothing to eat but hides. O ! Mary, I would cry and wish I had what you all wasted. Eliza had to go to Mr. Graves; we staid at Mr. Brien's. They had meat all the time. We had to kill little Cash, and eat him. We ate his entrails, and feet, and hide, and every thing about him. My dear cousin, you often say you can't do this and you can't do that; but never say you can't do any thing—you don't know what you can do until you try. Many a time had we the last thing on cooking, and did not know where the next meal would come from; but there was always something provided for us.

There were fifteen in the cabin that we were in, and one half of us had to lay in bed all the time.—There were ten died while were at the cabins. We were hardly able to walk. We lived on little Cash a week; and after Mrs. Brien would cook her meat and boil the bones two or three times, we would take them and boil them three or four days at a time. Mother went down to the other cabin and got half a hide, bringing it in snow up to her waist. It kept on snowing and would cover the cabins, do all we could to prevent it, so that we could not get out for two or three days at a time. We would have to cut pieces of the logs on the inside to make a fire with. The snow was five feet deep on the top of the cabin. I could hardly eat the hides. Father as we afterwards learnt, started out for us with provisions, but could not reach us, for the dreadful storms and deep snow, and after he had come into the mountains eighty miles, had to cache his provisions and go back on the other side to get a company of men to assist him. Hearing this they made up a company at Sutter's Fort, and sent out to our relief. We had not eaten any thing for three days; we were out on the top of the cabin, and saw a party coming. Oh, my dear cousin, you don't know how glad we were! One of the men we knew. We had traveled with him on the road.— They staid with us three days to recruit us a little; so that we could go back with them. There were twenty-one of us who left with them, but after going a piece, Martha and Thomas gave out, and the men had to take them back. Mother and Eliza and I came on. One of the party said he was a Mason, and pledged his honor that if he did not meet father he would go back and save his children. O ! Mary, that was the hardest thing yet—to leave the children in those cabins—not knowing but they would starve to death. Martha said, well Mother, if you never see me again, do the best you can.—The men said they could hardly stand it: it made them cry. But the men said it was best for us to go on and the children to be taken back. The men did so, and left for them at the cabin a little meat and flour. Mother agreed to leave them upon the pledge of Mr. Glover that he would return for them if we did not meet father,—which we did in five days. We went on over a high mountain as steep as stair steps in snow which was up to our waists. Little James walked all the way. He said every step he took he was getting nearer father and nearer something to eat. The Martens took the provisions the men had cached, and we had very little to eat. When we had traveled five days we met father with thirteen men on their way to the cabins. O, Mary ! you don't know how glad we were to see him. We had not seen him for five months. We thought we should never see him again. He heard we were coming and he made some sweet-cakes the night before at his camp to give us and the other children with us. He said he would see Martha and Thomas the next day. He went there in two days. They found some of the company eating those who had died; but Martha and Thomas had not had to do it. The men left the cabins with seventeen persons. Hiram Miller carried Thomas and father carried Martha, and they were caught in a storm that lasted two days and nights, and they had to stop that time. When they went on they found the Martens had taken their provisions, and they were four days without any thing. They went on again, and one of Donner's boys was with them, and the snow was up to their waists, and it kept on snowing so that they could hardly see the way. In all that time Thomas asked for something to eat but once. Father brought Martha and Thomas in to where we were. None of the men he had with him were able to go back to the cabins, their feet was froze so bad. So another company went out and brought all the persons in from there. They are all in now from the mountains but four, who are at a place called the Starved Camp, and a company is gone to their relief. There were but two families, of the whole number in the mountains, that got out safe. Our family was one of them. Mary, I have not told you one half of our troubles; but I have told you enough to let you know that you don't know what trouble is yet, and I hope never will such as we have seen. Thank GOD, we have all got in with our lives, and we are the only family that did not have to eat human flesh. We have lost everything, but I don't care for that. We have got through with our lives. But don't let this letter dishearten any from coming here. Don't take any Cut Offs, and bring nothing but provisions and just enough clothing to last till you get here.

My dear Cousin: We are all very well pleased with the country, particularly with the climate.— Let it be ever so hot a day, the night is always cool. It is a beautiful country. It is mostly in valleys and mountains. It ought to be a beautiful country to pay us for our troubles in getting to it. It is the greatest country for cattle and horses you ever saw. It would just suit Charley; for he could learn to be a bocarro [vaquero, Ed.],—that is, one who lassos cattle and horses. The Spaniards and Indians are great. They have a Spanish saddle, and wooden stirrups, and great long spurs, with the pricking part five inches in diameter. They could not manage the California horses without the spurs. They won't go on at all without they wear the spurs. They have little bells fastened to them to make a jingle. They blindfold the wild horses, get on to them, and then take off the blindfold, and let them run, and if the riders can't sit on them, they tie themselves on and let them run as fast as they can. One Indian will ride into a band of bullocks and throw the lasso on a wild one, and it being fastened to the horn of his saddle, he can hold it as long as he wants to do so. Another Indian throws his lasso on the feet of the bullock, and together, they throw him right over. The people here ride from eighty to one hundred miles a day on horseback. This country just suits father and I for riding. Some of the Spaniards have from 6 to 7,000 head of horses, and from 15 to 16,000 head of cattle. Tell the girls that this is the greatest place for marrying they ever saw, and that they must come to California if they want to marry . Tell ___ that ___ is engaged to be married. You all think this is a joke, but I tell you 'tis the real truth. Tell Doctor ___ that they doctor the funniest in this country that he ever saw. They grease the sick all over with mantaja [manteca, Ed.] and kill a bienna [gallina, Ed.] and cut it in four pieces, and put a great piece of fat carrina [carne?, Ed.] on the wrist, and kill a sheep and wrap the sick up in the skin. Father is now down at St. Francisco. He is going to write when he comes back. Give my love to all.— So no more at present, my dear cousin.

VIRGINIA E. B. REED.

Miss MARY C. KEYS, Springfield, Illinois.

Illinois Journal, 23 December 1847

CALIFORNIA CORRESPONDENCE [ CONTINUED. ]

NAPA VALLEY, Cal., 2d July, 1847.

DEAR SIR:

We have landed in California, at last, after great tribulation. The history of our journey, as well as some notices of this country, accompany this letter. I will add other notices of incidents and miscellaneous things, which I omitted in that communication.

Wheat sells here for one dollar per bushel. The call for wheat is limited. Large 3 year's old beef sells for $1 per quarter; and when retailed, at two cents per lb. Pork, the finest I ever saw, sells for 6 cts. per lb. In no country can hogs be raised with less trouble—supporting themselves without expense to the owner. Beef and pork can be put-up here to great advantage;—the finest salt in this world is found on the beach of this bay. Lumber for barrels, however, is rather scarce. You can go into a flock of a thousand sheep, and select and kill the best for $2 each. Butter is 50 cts. per lb.: cheese, 25 cents; chickens, 50 cents each; eggs, 50 cents per dozen. Hens lay and hatch the year round without any care. Turkeys are plenty on some farms. Flour is worth from $6 to $8 per 100 lbs.—owing to the scarcity of mills, and the want of machinery for cleansing the wheat. Horses sell from $6 to $30; wild mares, $6 to $10.

Vegetables can be grown here in perfection, but the seed must be put into the ground in the winter, and then they will mature before the dry weather comes on. The finest pumpkins I ever saw were here, and you can enjoy them the year round.— Watermelons can also be kept for a long period. I have eat them in December. Fine cabbage and lettuce are in perfection the first of May. Potatoes are raised in many places. Corn was in roasting ears on the Sacramento on the 6th of June. Beans were then large enough for eating. Onions grow very large and fine. Indeed, all the culinary vegetables can be raised in great abundance and excellence, by planting at the proper season.

Figs and Olives are not a certain crop, being delicate fruits. Oranges and Lemons have not been tried here; but they do well 3 or 400 miles below. I can make a living for my little family easier here than in the States; and while I am doing this, I am certain that they are enjoying good health. I do not look to the approach of the warm season with any dread. I have not to labor in summer to procure feed for stock in winter, while I am shaking with the ague or burning with fever. When the rainy season comes on, all I have to do, is now and then to see to my stock,—that is, to ride round and bring them together. I can get help without difficulty to plow, sow, reap, and get my wheat cleaned and housed; and if I want to sell any, the same help is at hand to take it to market. If I do not wish to take the oversight of my stock myself, I can employ a native to do it.

Our Sugar, Coffee and Molasses, come from the Sandwich Islands. Cotton and other goods come from home. These last articles are high; but competition will soon regulate business. Iron is worth 10 to 16 cents per lb. Ploughs bear a high price.

The wheat now is within a few days of cutting. It is more forward on the Sacramento. At Capt. Sutter's ranch two weeks past, he had 400 Digger Indians harvesting his wheat. His crop this year is estimated at 80,000 bushels.

Sonoma Valley west of this place about 12 miles, is a fine little valley, about 20 miles long and from 1 to 3 miles wide. At the mouth of this valley on the bay, is the town of Sonoma, which is fast improving by American emigrants, who came in here last fall. It is a pleasant place, but more subject to fogs from the sea than the Napa. The mountains on the west of Sonoma are low, and the fogs and cold winds have a fuller sweep from the ocean. It is not so with the Napa. On the west side, and between it and the Sonoma, there is a high range of mountains, which prevents sudden changes. The globe cannot present a healthier spot than this valley. Presuming that you have heard of these valleys, and as many of our friends are located in them, I have thought that a slight notice of them would be entertaining to you.

Napa Valley is the place where I am now residing with my family, at the house of Capt. George Yount, formerly of Missouri. Capt. Y. has been here for 15 or 16 years. He is known all over California for his honesty and hospitality. I have often seen a bullock a day consumed at his house, and sometimes two. There are more fat bullocks consumed at his house than at the Planter's House in St. Louis; and they are fatter than any ever seen there. The greatest objection to beef here is, that it is too fat. Napa Valley is about 30 miles long, and from one to three miles wide, and contains some of the finest land I ever saw; it is well watered, Napa Creek running through it. There is now in progress of building upon this creek, three flouring and one saw-mill. I admire this valley. No healthier place can be found—no fever, no ague, no sickness. The days are pretty hot, with cool nights. It is a fine location for fruit— apples, peaches, and grapes.

I do not want by any thing; I have said to be understood as encouraging persons to come here.— Far from it. If I like the country, others may and do dislike it. Many are dissatisfied and will leave it; but the country will lose little by their absence —except an outbreak of the Mexicans should take place, and in that case heads count. There is a great deal of difficulty in coming to this country, and particularly the last 300 miles of the road.— The worst is in crossing the mountains. For about 80 miles, you never saw a worse road, though 19-20ths of the wagons came through safe. The disasters of the company to which I belonged, should not deter any person from coming who wishes to try his fortune. Our misfortunes were the result of bad management. Had I remained with the company, I would have had the whole of them over the mountains before the snow would have caught them; and those who have got through have admitted this to be true.

I will refer to some of my unfortunate companions. Bayliss Williams began to fail before the company was out of provisions. Milton Elliott was well and hearty when he went to the cabins of the Donners. He helped Mrs. Donner to render as comfortable as possible their miserable abode. He was gone some ten or twelve days, and when he returned, was thin and weak, and in a few days died. He lived longer than Bayliss. James Smith was about the first who died of the boys. He gave up, pined away and died; he did not starve. John Denton left with the first company; he gave out on the way. I found him dead, covered him with a counterpane, and buried him in the snow, in the wildest of the wild portions of the earth. Here, too, C. T. Stanton, of Chicago, resigned his spirit to its Eternal Father, after he had labored and toiled, and finally sacrificed his life, to save his companions in distress. Some ten or eleven other unfortunate beings I was compelled to leave at the head of the Juba, on account of the neglect of Passed Midshipman Woodworth, to perform the part expected of him.

May God bless you and all my old friends about Springfield.

Your brother,

JAMES F. REED.

Mr. GERSHOM KEYS, Springfield, Illinois.