My father was an engineer by occupation: photography was his hobby. His early albums of black-and-white prints, taken from the 1930s onward, record happy memories -- days in the hills, and picnics with the family.

My father was an engineer by occupation: photography was his hobby. His early albums of black-and-white prints, taken from the 1930s onward, record happy memories -- days in the hills, and picnics with the family. When my father died in January 2007 at age 94, I inherited his photographic collection. This contained 35,000 colour slides, assembled over half a century, documenting his travels and observations. The family had a high opinion of his work, and agreed that these images were worth preserving. I undertook to have the transparencies digitized over the following years: this project was completed in June 2012. First, some background and recollections.

| The Photographer | Cameras and Accessories | Films and Development | Review, Labelling and Storage | Projection and Shows | Digitizing the Slides | Internet Library | Web Gallery |

My father was an engineer by occupation: photography was his hobby. His early albums of black-and-white prints, taken from the 1930s onward, record happy memories -- days in the hills, and picnics with the family.

My father was an engineer by occupation: photography was his hobby. His early albums of black-and-white prints, taken from the 1930s onward, record happy memories -- days in the hills, and picnics with the family.

The switch to colour slides apparently began with a business trip to South Africa in 1955. From then onward, his photo collection became a sort of personal log or diary, recording places visited and sights seen.

The switch to colour slides apparently began with a business trip to South Africa in 1955. From then onward, his photo collection became a sort of personal log or diary, recording places visited and sights seen.

Many of the early Scottish photos were taken on Sunday family outings. Douglas used to say that these excursions were his way to avoid telephone calls from company management on his rest day: but it is equally true that he and wife Kathleen shared a deep love of the outdoors (see image at left, at age 25, on a summer mountaineering holiday). This zest for travel found an ideal vehicle in the trailer-caravan: no place was too remote to visit, and accommodation expenses were modest. Douglas and Kathleen were active in local clubs, attending rallies around Britain as well as continental Europe, South Africa and the United States. Kathleen died in 1983. Douglas later remarried; and he and Jane travelled widely in North America, this time by RV (recreational vehicle).

The sheer number of slides that Douglas assembled is impressive: proof that the camera was a constant travel companion (see image at right, taken at his 94th birthday). Their subject matter reflects his abiding interest in the natural world and mankind's relationship to it.

In the early years, he photographed many landscapes. Family members were often requested to stand in the foreground, providing "scale" or "human interest". There was a definite preference for bright clothing -- a red windjacket, for example, to "brighten things up". Setting up the shot often took a while, but the resulting pictures were worth the wait.

Back in the 1950s, photography was not as easy as it is in these days of point-and-shoot digital cameras, with zoom, built-in flash and instant replay. In fact, it seems irrational for any present-day amateur photographer to be nostalgic about the "good old days". For example, to take a good photograph, it was necessary to perform several important steps before pressing the shutter-release button, including: (1) setting the distance to subject (to provide focus); (2) selecting shutter speed (to arrest motion); and (3) selecting aperture (to control depth of field)

-- these last two settings often seemed to work at cross-purposes!

-- these last two settings often seemed to work at cross-purposes!

I think Douglas started his slide collection using a Voigtländer Vito B. He used a portable exposure meter, but I don't remember whether he also had a range-finder. The flash gun was another separate device, to be clipped onto the camera before use.

Douglas's next camera was a

Zeiss Ikon Contaflex,

with through-the-lens viewing. Focusing was done directly in the viewing area. Another convenience was the exposure meter, built-in to the camera body, although the user still had to set speed and aperture manually. The lens was removable, with an exterior screw-thread for fitting close-up, colour correction and polarising filters. Douglas later bought exchangeable wide-angle and telephoto lenses, housed in a fine leather carrying-case.

Douglas's next camera was a

Zeiss Ikon Contaflex,

with through-the-lens viewing. Focusing was done directly in the viewing area. Another convenience was the exposure meter, built-in to the camera body, although the user still had to set speed and aperture manually. The lens was removable, with an exterior screw-thread for fitting close-up, colour correction and polarising filters. Douglas later bought exchangeable wide-angle and telephoto lenses, housed in a fine leather carrying-case.

After many years of service, the Zeiss was replaced by a Minolta: first an

XD-7, then an

X-700

; both models were capable of automatic exposure setting, but still had to be focussed manually.

Other acquisitions included specialized lenses for macro, zoom and telephoto work

After many years of service, the Zeiss was replaced by a Minolta: first an

XD-7, then an

X-700

; both models were capable of automatic exposure setting, but still had to be focussed manually.

Other acquisitions included specialized lenses for macro, zoom and telephoto work

-- the accessories bag grew larger! Photos could now be taken faster, and with more confidence, but the underlying technology had scarcely changed.

-- the accessories bag grew larger! Photos could now be taken faster, and with more confidence, but the underlying technology had scarcely changed.

Initially, colour slide (transparency) film was very slow (ISO 8 and 25) : on overcast days, shutter speeds could be 1/30th second or more, risking camera shake. Furthermore, an accurate exposure was especially important. When making prints from a negative film, there was an opportunity to compensate for over- or under-exposure. But slide film was bulk-developed by machine, so "what you shot is what you got".

Douglas used Kodakchrome slide film, which was developed in specialized plants: each roll held 36 (optionally 24) exposures. A prepaid mailing envelope was included with the film spool; the exposed film was sent off by post; then came the days of patient waiting until the developed slides arrived. Great was the angst if a roll was ever lost.

Douglas used Kodakchrome slide film, which was developed in specialized plants: each roll held 36 (optionally 24) exposures. A prepaid mailing envelope was included with the film spool; the exposed film was sent off by post; then came the days of patient waiting until the developed slides arrived. Great was the angst if a roll was ever lost.

Eventually, Kodak brought higher film "speeds" to market (ISO 64 and 200), providing an acceptably low graininess. For a time, Douglas experimented with Ektachrome film, which was "faster" and easier to have developed, but he was not satisfied with the results.

When the processed slides arrived, they first had to be checked for quality: "duds" were promptly consigned to the trash can. Due to their small size (the useable image area of a mounted slide is just 32mm by 22mm), an illuminated magnifier was used.

When the processed slides arrived, they first had to be checked for quality: "duds" were promptly consigned to the trash can. Due to their small size (the useable image area of a mounted slide is just 32mm by 22mm), an illuminated magnifier was used.

Next, the images were hand-annotated with location and date (plus subject matter, when the photo was not self-explanatory): this information was written on the cardboard mounts, and has been utterly essential to me for the digitization project.

Next, the images were hand-annotated with location and date (plus subject matter, when the photo was not self-explanatory): this information was written on the cardboard mounts, and has been utterly essential to me for the digitization project.

The processed slides arrived in a protective cardboard box, which was adequate for initial handling. For long-term storage they were transferred to large-capacity units: either stackable plastic trays or metal boxes, both types equipped with internal dividers.

After each trip, the family were treated to a slide show. This contained the best and most representative images, and might last an hour or so. By keeping these "selected sets" separate, the show could easily be repeated.

During the show, Douglas supplied a running narrative. His memory recall was excellent: he might also refresh in advance by reviewing the annotations. In later life, special shows were prepared on a given theme, which he researched and illustrated using images drawn from across his collection: for these, he prepared written notes.

During the show, Douglas supplied a running narrative. His memory recall was excellent: he might also refresh in advance by reviewing the annotations. In later life, special shows were prepared on a given theme, which he researched and illustrated using images drawn from across his collection: for these, he prepared written notes.

For best results, shows were held at night: during daylight hours, the room had to be thoroughly blacked-out. Images were projected onto a portable screen, which came in its own carrying case. The earliest projectors were hand-operated, being superseded by more powerful fan-cooled Kodak machines with automatic advance and focussing, capable of producing a bright image 5 feet across. For these projectors, slides were loaded into removable "carousels", holding up to 140 (originally 80) mounts: with several pre-loaded carousels, preparation time for any show could be reduced to a minimum. One inconvenience: the high-intensity light bulbs had a short life, sometimes failing in mid-show and delaying proceedings until they were cool enough to be removed and replaced.

For best results, shows were held at night: during daylight hours, the room had to be thoroughly blacked-out. Images were projected onto a portable screen, which came in its own carrying case. The earliest projectors were hand-operated, being superseded by more powerful fan-cooled Kodak machines with automatic advance and focussing, capable of producing a bright image 5 feet across. For these projectors, slides were loaded into removable "carousels", holding up to 140 (originally 80) mounts: with several pre-loaded carousels, preparation time for any show could be reduced to a minimum. One inconvenience: the high-intensity light bulbs had a short life, sometimes failing in mid-show and delaying proceedings until they were cool enough to be removed and replaced.

Given the industrial scale of this project, the following notes may be of interest.

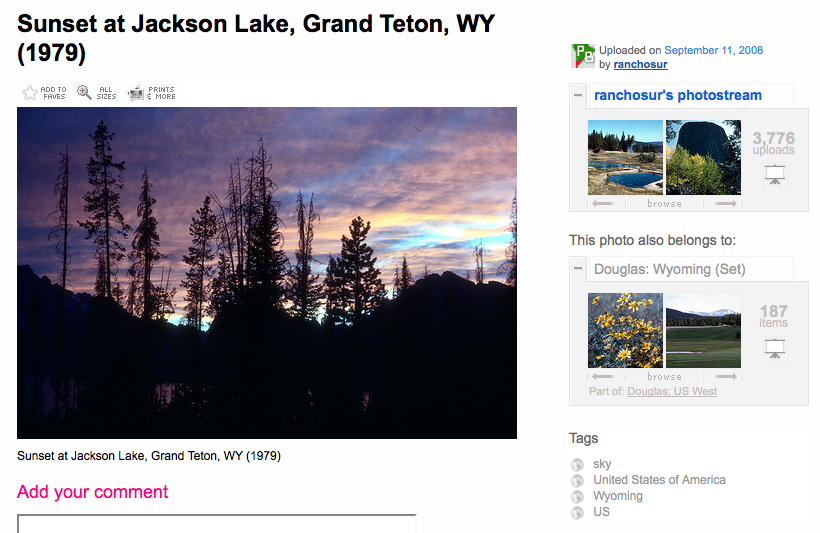

The objective is to share Douglas's photos in an organized way, where they are available for search/query by all the family. For this purpose, I have registered for the Flickr! Pro service, under the pseudonym <The Douglas Campbell Show>. At the same time, it became possible to share smaller copies of the photos with the general public: this has generated a fruitful exchange of background information.

Product Suitability

The "good news" is that Flickr! retains a large part of the image metadata. The following tags are visible to the end-user, and available for querying: Headline, Description, Keywords, City, State, Country, ISO Country Code.

Proof-of-concept testing revealed a few shortcomings, but these were either minor or could be worked around. Specifically:

(a) IPTC Creation Date is not visible to the user: but I always include the creation year in the Headline. Flickr!, being oriented to digital photography, shows the upload date and the EXIF Capture Date. iView has a special function to modify the latter, but it did not produce the desired result. Flickr! also offers a manual override. However, neither mechanism is practical for such a large collection.

(b) IPTC Location is not visible to the user: but, I usually include an abbreviated form in the Headline.

(c) When present, IPTC Title replaces IPTC Headline. This is improper, because the IPTC standard defines this tag as a record identifier. I have used it when Douglas serial-numbered his mounts. As such, it has no value to the user, and can be deleted up-front.

(d) When absent, IPTC Description is set to the same value as IPTC Headline. This is not harmful, but it is distracting: I am deleting the duplicates manually from Flickr.

|

Organization The image database is organized into Sets by Country (State in the case of USA), which are in turn aggregated into Collections (e.g. US Southwest). For a few Sets (Scotland, Virginia) the final image count runs into thousands; initial tests showed that it could be cumbersome to administer Flickr! Sets larger than a few hundred images. Therefore I have chosen to subdivide all Sets by calendar year: this should also be more manageable for the visitor. In general, the following folders are not open to public access: Preparation To protect the privacy of subjects in publicly accessible images, the Headline and Description tags usually do not identify individual people: personal names have been omitted, or abbreviated to their initial letter. Similarly, precise addresses are sometimes replaced by a more generic term (e.g. the town name). Since many of the human subjects have already died, this policy may be progressively relaxed. (Note: The master iView record includes a tag for personal names, but it is not used by Flickr!.) Upload (a) Split each scanned batch into separate folders, according to the database structure, using iView. The intermediate JPEG image is high quality, 1200 pixels wide by 900 pixels high, maintaining the original proportions. This resolution provides reasonably fast image upload, while ensuring good visual quality in the different Flickr! contexts. (b) Use iView to delete all IPTC Title values from the intermediate files. This must be a physical update, not simply a catalog modification. (c) Upload one folder at a time via the Flickr! website, using the native batch tool. Check the Photostream, then add images to their respective Set. (d) Adjust privacy controls for unrestricted viewing and commenting at this URL: http://www.flickr.com/photos/thedouglascampbellshow/. |

|

I started the digitization project using the following 28 existing shows. The web pages were generated by Adobe Lightroom. Documentation was based on the annotations on each mount: sometimes I added a short explanatory note, using my own knowledge or other sources. Accompanying notes (Douglas's memory aids) were transcribed: they are marked like this -- /*/

PARTS OF THIS SECTION ARE NO LONGER AVAILABLE. PLEASE VISIT <The Douglas Campbell Show>.

Note: All slides are bulk-processed at high resolution by a commercial lab. Most images are presented "as delivered", without any retouching or adjustment. In some cases, software manipulation (Photoshop) has been used to correct exposure. In a few cases, where colours are plainly incorrect, or images are very grainy, individual re-scanning will be needed.

Duncan S. Campbell

rev. June 2012